As a loving pet owner, few things are as frightening as seeing your dog or cat in distress. When an emergency strikes, knowing what to expect at the veterinary clinic can help alleviate some anxiety and prepare you for the critical steps ahead. This guide will walk you through the concept of “Vet Triage” – how veterinarians prioritize and manage urgent cases – focusing on two common and critical emergencies: acute respiratory distress and seizures. Understanding these processes can empower you to act quickly and effectively alongside your veterinary team. For immediate concerns, it’s always best to seek care from urgent vets for pets.

Understanding What “Vet Triage” Means for Your Pet

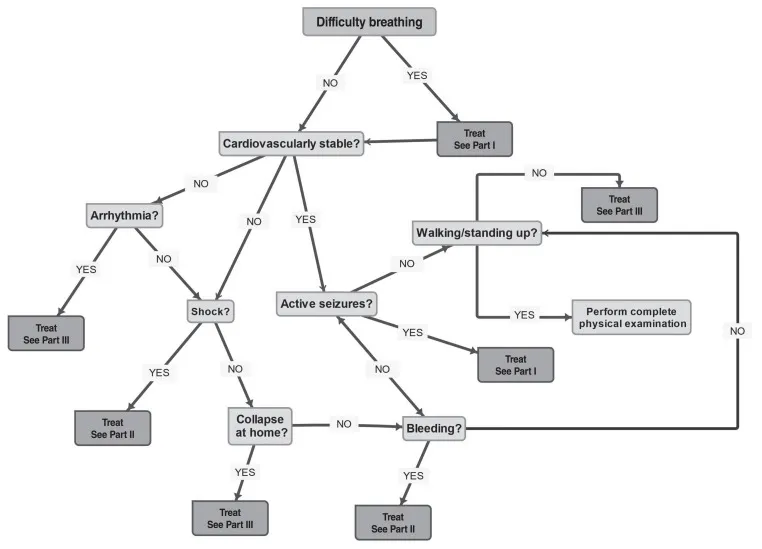

Triage is a systematic approach where veterinary staff quickly assess and prioritize patients based on the severity of their condition and their need for immediate medical attention. In a busy emergency setting, not all pets can be seen simultaneously, so triage ensures that the most critically ill animals receive care first. This isn’t about deciding who has the best chance of survival, but rather identifying those who need immediate intervention to stabilize their condition.

When your pet arrives at an emergency vet, a rapid but thorough physical examination will be performed to classify their urgency. This often uses a system similar to the one shown in veterinary charts, where conditions are color-coded (red for immediate care, orange for urgent, yellow for non-critical but needing attention, and green for stable conditions). This quick assessment helps the team understand if your pet is stable enough for diagnostics or if immediate life-saving interventions are required before further work-up. It’s important to remember that basic stabilization is often the first and most crucial step, sometimes even before referral to a specialized facility.

A simplified flowchart illustrating veterinary triage categories based on severity and body systems, guiding initial assessment and intervention steps.

A simplified flowchart illustrating veterinary triage categories based on severity and body systems, guiding initial assessment and intervention steps.

Recognizing and Managing Acute Respiratory Distress in Dogs and Cats

Respiratory distress is a severe emergency where your pet struggles to breathe. This condition should never be delayed for referral without initial stabilization, as pets in severe respiratory distress can deteriorate very quickly, sometimes even during transport. Prompt action by a veterinarian to stabilize breathing is paramount.

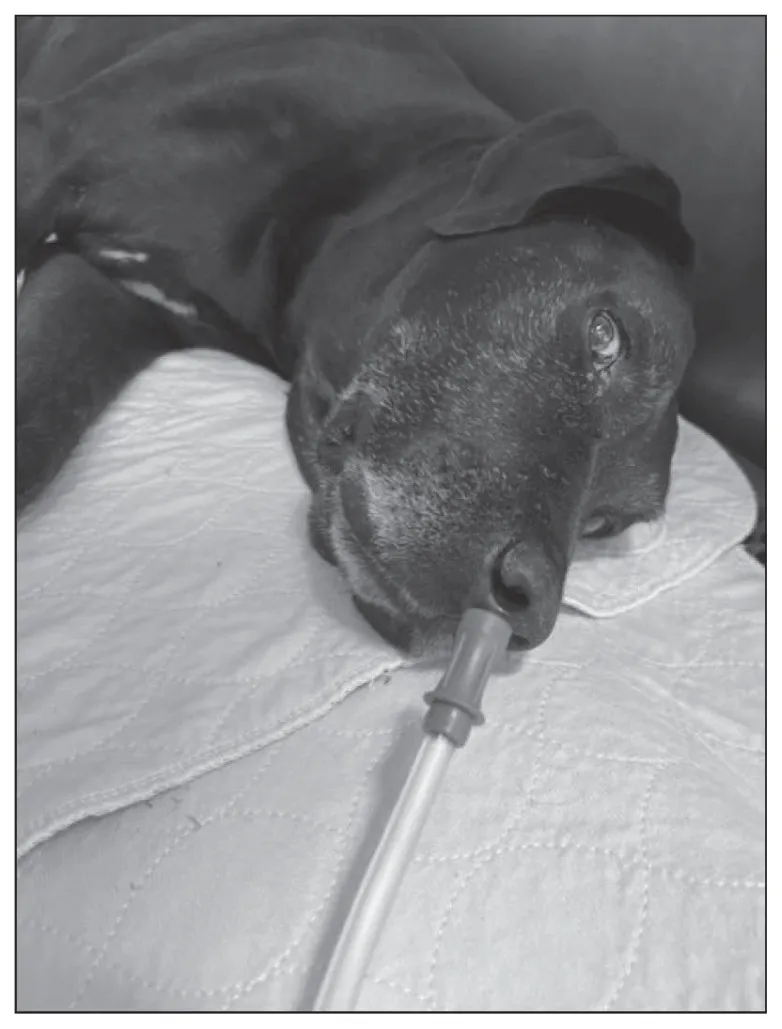

Step 1: Providing Oxygen Safely

When a veterinarian identifies respiratory distress, the absolute first priority is to provide oxygen therapy while minimizing stress to your pet. Stress can worsen breathing difficulties, so a calm and efficient approach is essential. The fastest initial option is often “flow-by” oxygen therapy, where oxygen is gently directed towards your pet’s nose and mouth. This allows for concurrent examination while providing vital support.

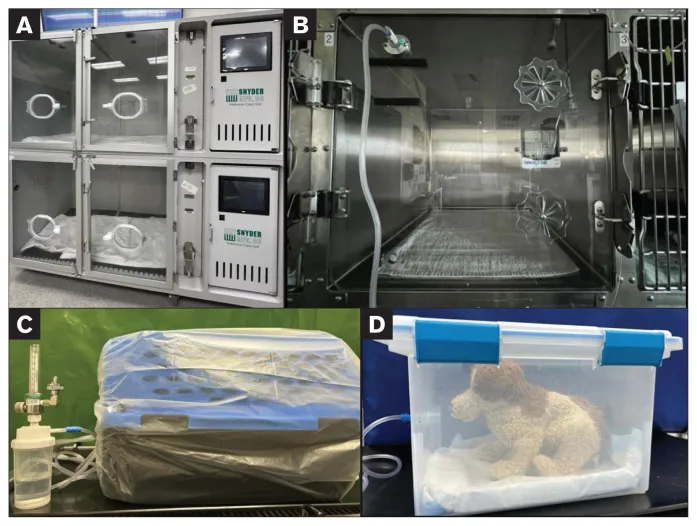

For smaller dogs and cats, placing them in an oxygen cage or chamber is a highly effective and low-stress method to administer oxygen. While not all general practices have dedicated, commercial oxygen cages, many can adapt a standard cage with a plastic door or use smaller incubators. Creative solutions might even include placing a pet carrier inside a plastic bag filled with oxygen or using a plastic box with appropriate ventilation holes as a temporary chamber. It’s crucial to monitor the temperature within these enclosures, as they can quickly become hot or humid, especially for panting dogs or larger pets. Veterinarians will always ensure sufficient exhaust holes to vent carbon dioxide and heat, maintaining a safe environment.

A veterinarian administers flow-by oxygen therapy to a dog in respiratory distress, providing vital support with minimal restraint.

A veterinarian administers flow-by oxygen therapy to a dog in respiratory distress, providing vital support with minimal restraint.

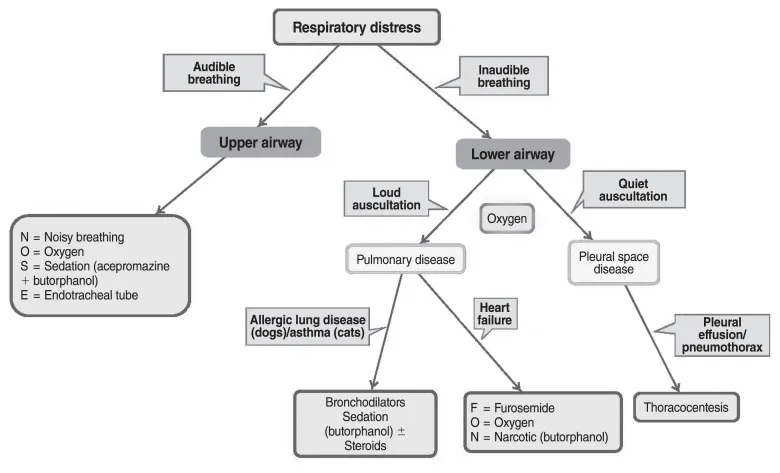

Step 2: Identifying the Type of Breathing Problem

Once your pet is receiving oxygen, the next critical step for the veterinarian is to categorize the type of respiratory distress: is it originating from the upper airways or the lower airways? The distinction guides the specific emergency treatments.

Upper Airway Disease

Upper airway disorders affect the nose, throat, and trachea (windpipe). They are typically characterized by noisy breathing sounds like stertor (snoring-like) or stridor (high-pitched wheezing on inspiration), visible anxiety, and sometimes a bluish tint to the gums (cyanosis) due to lack of oxygen.

Common Causes:

- In Dogs: Brachycephalic airway syndrome (common in breeds like Pugs and Bulldogs), laryngeal paralysis (often seen in Labrador Retrievers and other large breeds), and collapsing trachea (frequent in small breeds such as Yorkshire Terriers).

- In Cats: Upper airway problems are less common but can be caused by masses in the mouth or throat, secondary to viral infections, or nasopharyngeal polyps in younger cats and kittens. Trauma or certain types of cancer can also lead to laryngeal paralysis in felines.

Emergency Stabilization for Upper Airway Disease (The “NOSE” Mnemonic):

Veterinarians often use the mnemonic “NOSE” to guide acute treatment:

- Noisy breathing means:

- Oxygen: Administered with minimal stress, as described previously.

- Sedation: Medications like butorphanol and/or acepromazine help calm the pet, reducing anxiety and thus lowering oxygen demand. Dexmedetomidine may also be used for sustained sedation.

- Endotracheal Tube Placement (Intubation): If oxygen and sedation aren’t enough, intubation might be necessary to establish a clear airway. This is a critical step in severe cases and vets won’t hesitate if the pet’s condition warrants it. Anesthetics like propofol or alfaxalone are used to facilitate this procedure, keeping the pet comfortable and relaxed for at least 30 to 60 minutes. Inhalant anesthetics are often avoided due to risks of low blood pressure or breathing depression. Once the airway is secured, the distress often resolves.

Practice Tips for Owners:

- Hyperthermia: Upper airway obstructions can interfere with a pet’s ability to cool down. Overheating (hyperthermia) can mimic respiratory distress, especially in obese, stressed, or brachycephalic animals, or those in oxygen cages. Your vet will monitor body temperature closely.

- Inflammation: Anti-inflammatory medications, such as a low dose of steroids, might be given to reduce swelling in the airways.

If your pet is experiencing these severe symptoms, it’s crucial to seek help from urgent pet vets immediately.

Lower Airway Disease

Lower airway disease affects the lungs and smaller airways (bronchi and bronchioles). Dogs with lower airway disease typically show an increased respiratory rate and sometimes a cough, while cats may not always have an obvious cough. Both species can exhibit open-mouthed breathing and significantly increased effort. Unlike upper airway cases, where noises from the throat can make it hard to hear the lungs, listening to the chest (auscultation) is vital in lower airway disease to determine if the lung sounds are “loud” or “quiet.”

“Loud” Auscultation (Pulmonary Parenchymal Disease):

When the veterinarian hears crackles or wheezes in the chest, it indicates involvement of the lung tissue itself (pulmonary parenchyma).

- In Dogs, common causes include:

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Fluid buildup in the lungs not caused by heart failure. This can be triggered by toxin inhalation, prolonged seizures, electrocution, or systemic inflammatory conditions like pancreatitis. Upper airway obstruction is also a common cause.

- Cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Fluid in the lungs due to heart failure, more common in middle-aged or older dogs with conditions like myxomatous mitral valve disease or dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Pneumonia: Inflammation of the lungs, often bacterial, viral, or fungal. Aspiration pneumonia (inhaling vomit or foreign material) is also a concern, especially in brachycephalic breeds.

- In Cats, common causes include:

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Similar causes as in dogs, including toxin inhalation, prolonged seizures, or systemic inflammation.

- Cardiogenic pulmonary edema: Often due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the most common heart disease in cats, typically affecting middle-aged felines.

- Feline Asthma: An inflammatory condition leading to airway obstruction, often characterized by acute onset of open-mouthed breathing and coughing (which owners might mistake for hairball retching).

- Pneumonia: Less common than in dogs, but can occur, especially in younger cats with viral infections or as a secondary complication to feline asthma.

Emergency Stabilization for “Loud” Auscultation:

For pets with severe breathing difficulties and “loud” lung sounds, veterinarians will prioritize stabilization before extensive diagnostics like radiographs (X-rays). A common “cocktail” of treatments aims to alleviate distress:

- Oxygen Therapy: As in upper airway cases, providing oxygen is critical.

- Furosemide: A diuretic, often given for suspected cardiogenic pulmonary edema to remove excess fluid from the lungs. It also has some bronchodilatory effects.

- Butorphanol: A mild sedative and pain reliever that helps reduce anxiety and respiratory effort.

- Bronchodilators and Steroids: For suspected feline asthma, bronchodilators (like terbutaline) can quickly open airways, and steroids can reduce inflammation. Injectable steroids may be used, though inhaled forms are also an option.

One dose of these medications is unlikely to cause harm and can be life-saving. Your vet will make an informed decision based on your pet’s presentation.

A detailed veterinary flowchart outlining the systematic stabilization process for dogs and cats experiencing respiratory distress, from initial oxygen to specific treatments.

A detailed veterinary flowchart outlining the systematic stabilization process for dogs and cats experiencing respiratory distress, from initial oxygen to specific treatments.

“Quiet” Auscultation (Space-Occupying Disease):

When a pet in respiratory distress has “quiet” or muffled lung sounds, it often suggests a problem outside the lung tissue, typically fluid or air accumulating in the chest cavity, compressing the lungs. The most common diagnoses are pneumothorax (air in the chest) or pleural effusion (fluid in the chest). These pets may show a “paradoxical” breathing pattern, where the abdomen and chest move in opposite directions.

- In Dogs, common causes include:

- Pneumothorax: Can be spontaneous (due to lung bullae, neoplasia, or chronic lung disease) or traumatic (motor vehicle accidents, bite wounds).

- Pleural Effusion: Fluid can accumulate due to various reasons, including toxins (e.g., anticoagulant rodenticides causing internal bleeding), heart failure, chylothorax (lymphatic fluid), trauma, cancer, or pyothorax (pus).

- In Cats, common causes include:

- Pneumothorax: Also traumatic or spontaneous, often secondary to underlying lung diseases like asthma, cancer, or infections.

- Pleural Effusion: Most commonly due to congestive heart failure or neoplasia, but can also be pyothorax, chylothorax, or feline infectious peritonitis.

Emergency Stabilization for “Quiet” Auscultation (Thoracocentesis):

The primary way to stabilize a pet with pneumothorax or pleural effusion is therapeutic thoracocentesis. This procedure involves inserting a needle into the chest cavity to remove the accumulated air or fluid, immediately relieving pressure on the lungs.

- Your vet will typically position your pet in sternal recumbency (on its chest) with oxygen. Sedation might be used to minimize stress.

- The fur will be clipped, and the skin sterilized.

- A sterile needle or butterfly catheter with tubing and a syringe will be used to carefully aspirate (draw out) the air or fluid. This can be done blindly or with ultrasound guidance.

- The vet will continue to remove air or fluid until negative pressure is achieved, indicating that the pressure has been relieved. Fluid samples will be collected for analysis to determine the underlying cause.

This procedure can dramatically improve your pet’s breathing almost immediately. If continuous air leakage occurs (e.g., from a persistent lung tear), a more invasive thoracostomy tube might be necessary. If your cat is struggling to breathe, finding an cat emergency vet near me is paramount.

A veterinary oxygen cage provides a controlled environment for a pet in respiratory distress, aiding stabilization and recovery.

A veterinary oxygen cage provides a controlled environment for a pet in respiratory distress, aiding stabilization and recovery.

Preparing Your Pet for Referral (Respiratory Distress)

The general rule for respiratory emergencies is to refer your pet only after their breathing distress has been significantly stabilized. Transporting an animal in severe respiratory crisis can be fatal. Key steps before transfer include:

- Following the NOSE protocol for upper airway disease.

- Performing thoracocentesis for pleural effusion or pneumothorax, removing as much air or fluid as possible.

- Administering appropriate medications as described (oxygen, diuretics, sedatives, bronchodiloids).

- Giving additional sedation (e.g., butorphanol) to ensure a calm journey.

- Recording all medications given, their doses, and timing, along with any thoracocentesis results (volume removed, side).

- For oxygen-dependent pets, considering a portable oxygen tank or a carrier within a plastic bag filled with oxygen for longer trips, if permitted and safe.

- If a continuous pneumothorax is present, inserting a thoracostomy tube may be necessary for ongoing drainage during transit.

- Crucially, the referral institution must be alerted about your pet’s incoming status so they can be prepared for immediate continuation of care.

What to Do When Your Pet Has Seizures

A seizure is a sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbance in the brain, leading to changes in behavior, movement, or consciousness. Two critical emergency situations related to seizures are Status Epilepticus (SE) and Cluster Seizures (CS).

- Status Epilepticus (SE): Seizure activity lasting longer than 5 minutes, or three or more seizures within 24 hours without your pet fully recovering consciousness between episodes.

- Cluster Seizures (CS): Two or more seizures within 24 hours, but with your pet returning to a normal mental state between episodes.

Emergency cases can range from pets actively seizing to those that just had a seizure. Signs can include full-body convulsions, excessive drooling, altered consciousness, urination or defecation, or vocalization. Seizures can also cause secondary issues like hyperthermia (overheating) or lung crackles (due to non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema). Cats’ seizures can often appear more violent. After a seizure (the postictal phase), pets might be wobbly (ataxic), have temporary neurological deficits, be disoriented, or even comatose. Others might seem normal or slightly hyperactive after cluster seizures.

Step 1: Is Your Pet Actively Seizing Now?

If your pet is actively seizing, the immediate priority for your veterinarian is to stop the seizure.

Initial Veterinary Actions:

- Topical Toxin Management: If a cat was exposed to a topical medication (like permethrin) known to cause seizures, they will be immediately bathed with dish soap and lukewarm water to limit further absorption. Medications like methocarbamol or benzodiazepines (diazepam or midazolam) may be administered.

- No IV Catheter: If an intravenous (IV) catheter cannot be placed immediately, medications like midazolam (intranasally) or diazepam (rectally) can be given to quickly try and stop the seizure. These doses can be repeated a few times if needed.

- IV Catheter in Place: With an IV catheter, diazepam or midazolam are administered intravenously and can be repeated. Long-acting anti-epileptic drugs like levetiracetam (as a loading dose) and phenobarbital are often started concurrently, regardless of the immediate response to benzodiazepines.

- Persistent Seizures: If seizures continue, a continuous rate infusion (CRI) of diazepam or midazolam may be started. For very severe, refractory seizures, a propofol CRI can induce anesthesia to stop the seizure activity, carefully monitored to minimize side effects, especially in cats (who can develop anemia).

Step 2: Understanding Why Seizures Happen

Once the seizure activity is controlled, the next crucial step for the veterinary team is to determine the underlying cause. Seizures can be categorized as either systemic/metabolic (problems outside the brain) or intracranial (problems within the brain).

Common Causes:

- Systemic/Metabolic:

- Blood Sugar Imbalances: Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) or hyperglycemia (high blood sugar).

- Electrolyte Abnormalities: Low calcium (hypocalcemia) or abnormal sodium levels.

- Toxin Ingestion: Various toxins can cause seizures, including antifreeze, certain recreational drugs, specific rodenticides, sago palm, or xylitol (in dogs), and permethrin or fipronil (in cats).

- Organ Disease: Liver disease (e.g., portosystemic shunt) or kidney failure (uremic encephalopathy).

- Blood Disorders: Severe anemia or low platelet counts leading to intracranial bleeding.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Thiamine deficiency (more common in cats).

- Intracranial (Brain-Related):

- Tumors: Various types of brain tumors.

- Cerebrovascular Disease: Strokes (infarcts or hemorrhage).

- Trauma: Head injuries.

- Meningoencephalitis: Inflammation of the brain and its surrounding membranes.

- Congenital Malformations: Brain abnormalities present from birth.

- Idiopathic Epilepsy: Seizures with no identifiable underlying cause (often genetic).

- Infectious Diseases: Various bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections affecting the brain.

Signalment and History: Your veterinarian will gather a thorough history, including previous seizure activity, current medications, seizure onset and duration, what your pet was doing before the seizure, other medical conditions, and any potential toxin exposures. Breed, age, and travel history can provide valuable clues.

Emergency Stabilization for Systemic/Metabolic Causes:

Beyond anti-epileptic drugs, the vet will perform baseline blood tests (electrolytes, glucose, PCV/TP, and possibly a chemistry panel) to identify systemic causes. Two treatable causes that are immediately addressed are:

- Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Sugar): If blood glucose is low, a dextrose solution will be given intravenously. This can prevent seizures or stop persistent ones.

- Hypocalcemia (Low Calcium): Common during pregnancy or lactation, or due to hypoparathyroidism. Calcium gluconate is administered slowly intravenously while monitoring the heart with an ECG. Understanding vets for pets prices for these types of emergency treatments can be helpful for pet owners.

Step 3: Additional Stabilization for Seizures

Beyond stopping the seizure and addressing immediate metabolic causes, veterinarians will take further steps to stabilize your pet.

Temperature

Prolonged seizure activity can cause a significant increase in body temperature (hyperthermia), which can be dangerous.

- Emergency Stabilization: If your pet’s temperature is very high (above 105°F or 40.6°C), cooling measures will be initiated. These might include cool compresses or intravenous fluids. Cooling will be stopped once the temperature reaches a safe level (around 103°F or 39.4°C), as over-cooling can also be harmful. Typically, once seizures are controlled, body temperature tends to normalize.

Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)

Prolonged seizures can lead to swelling in the brain (cerebral edema), which increases pressure inside the skull. Alternatively, an underlying brain condition (like a tumor) can cause both increased ICP and seizures.

- Recognizing Signs: Elevated ICP is suspected if your pet is lethargic, stuporous, has fixed or dilated pupils that don’t respond to light, or exhibits a combination of a slow heart rate (bradycardia) and high blood pressure (hypertension).

- Emergency Stabilization: Medications like mannitol or hypertonic saline (a concentrated salt solution) can be given intravenously. These drugs help draw fluid out of the brain, reducing swelling and ICP. Careful monitoring of electrolyte levels is essential, especially with repeated doses.

Lung Crackles

If your pet continues to have lung crackles or increased breathing rate and effort even after the seizure has stopped, the primary concerns are seizure-induced non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs due to the brain event) or aspiration pneumonia (inhaling fluid or vomit during the seizure).

- Emergency Stabilization: Any respiratory distress will be treated as outlined in the previous section on acute respiratory distress, prioritizing oxygen and appropriate medications.

Long-Term Outlook and Referral (Seizures)

For pets with status epilepticus or cluster seizures, owners need to understand several key points:

- Lifelong Medication: Unless the seizures are caused by a treatable toxin, lifelong anti-seizure medications are often required to manage the condition.

- Goal of Treatment: The long-term objective is usually to reduce the frequency and intensity of seizures, rather than to eliminate them entirely (except in toxin-induced cases).

- Adherence: Medications, often oral and sometimes multiple types, must be given daily at regular times for effective control.

Preparing Your Pet for Referral (Seizures):

Just like with respiratory distress, referral for seizures should occur after the seizures have stopped, and your pet’s blood glucose and body temperature are stable.

- Medication: At least one dose of a long-acting anti-epileptic medication should be administered before transfer.

- IV Access: If possible, ensure an IV catheter is in place for easy administration of further treatments during transit or upon arrival.

- Hypoglycemia: Do not transport a hypoglycemic animal. If hypoglycemia is present and transport will be long, provide oral or IV dextrose.

- Intracranial Pressure: If your pet has reduced consciousness, consider giving mannitol before referral to help reduce intracranial pressure.

- Communication: Always communicate with the referral institution, providing an accurate update on your pet’s status and any treatments given. This helps them prepare and manage client expectations regarding costs and prognosis. In such critical moments, seeking immediate vet urgent care is crucial.

Conclusion

Understanding “vet triage” and the initial stabilization steps for common emergencies like respiratory distress and seizures can significantly impact your pet’s outcome. While these situations are undoubtedly stressful, knowing that veterinarians follow a systematic, evidence-based approach to prioritize and treat life-threatening conditions can provide some reassurance. Prompt action on your part to seek veterinary care, combined with the expert efforts of your veterinary team, gives your beloved companion the best chance for recovery. Always consult your veterinarian for specific medical advice and emergency planning, as every pet and situation is unique.