In the frigid winter of 1925, a deadly diphtheria outbreak gripped Nome, Alaska, threatening the lives of its isolated community, especially its children. With an antitoxin desperately needed and the nearest supply point in Nenana, an incredible 674 miles away by rail, air travel was impossible due to an approaching blizzard. The only hope for delivering the life-saving serum in time rested on a relay of brave sled dog teams, an epic endeavor that would forever be etched in history as the “Great Race of Mercy.” While the lead dog of the final, triumphant leg, Balto, garnered widespread fame, many historians and dog sledding enthusiasts argue that the true hero of this harrowing journey was Leonhard Seppala’s lead dog, Togo. The remarkable odyssey of Togo, a 12-year-old Siberian Husky, and his musher, Seppala, saw them traverse an astonishing 264 miles—a distance far exceeding that of any other team—making their contribution undeniably pivotal to the success of the mission. To truly appreciate the magnitude of this achievement, we must delve into the true story of Togo, a canine legend whose unparalleled endurance, intelligence, and spirit saved a town. For a more detailed account of the events, explore the togo dog real story.

From a Troublesome Pup to a Legendary Lead Dog

Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian immigrant, arrived in Alaska in 1900, quickly establishing himself as one of Nome’s most formidable mushers. At this time, the dominant sled dog breeds were sturdy Alaskan Malamutes or various mixed breeds. However, the landscape of Alaskan sled dog racing began to shift with the arrival of the first Siberian Huskies, brought to Nome by Russian fur trader William Goosak. These smaller, yet incredibly resilient dogs, surprised many by securing a third-place finish in the 1909 All-Alaska Sweepstakes race. The following year, an all-Siberian team led by “Iron Man” Johnson took first place, setting a course record that still stands, solidifying the reputation of these scrappy Siberians as exceptional sled dogs.

Togo’s own journey began in 1913, reportedly born to a dam named Dolly, a foundational bitch in the breed’s development. As a puppy, Togo was undersized and plagued by health issues, leading Seppala to initially deem him unfit for his prized kennel, home to some of Nome’s finest sled dogs. Seppala gave the pup away to a neighbor, but Togo’s indomitable spirit shone through. He famously flung himself through a glass window, escaping back to Seppala’s side, a clear testament to his desire to be with his true owner. Seppala, seemingly stuck with the mischievous pup, soon found his initial judgment challenged.

As Togo matured, he became utterly captivated by the working sled dogs around him. Too young for a harness, he would often break free to run alongside Seppala’s teams during training, much to his owner’s initial frustration. His penchant for daring escapades once led to a mauling when he encountered a team of much larger Malamutes. Despite the challenges, Seppala observed an undeniable drive and intelligence in the young dog. Exasperated yet intrigued, Seppala made a pivotal decision: he put an eight-month-old Togo into a harness and hooked him into the team. That day, Togo not only ran an astonishing 75 miles but also worked his way up to the lead position, displaying a natural talent and leadership that Seppala had long sought. It became clear that Seppala had unwittingly found the perfect lead dog he had always yearned for, setting the stage for Togo’s incredible sled dog story.

Togo in single lead on a snowy trail in 1921

Togo in single lead on a snowy trail in 1921

Togo and the Heroic 1925 Nome Serum Run

Over the years, Togo’s reputation for tenacity, strength, endurance, and intelligence spread across Alaska, solidifying his status as Seppala’s most prized lead dog. Together, dog and man became an inseparable force, leading Seppala’s team to victory in the All-Alaska Sweepstakes in 1915, 1916, and 1917, among countless other races and excursions.

By the time the diphtheria outbreak struck Nome in January 1925, Togo was 12 years old and Seppala 47. Both were considered past their prime, yet with the fate of Nome hanging in the balance, the seasoned duo was recognized as the community’s best, and perhaps only, hope. As deaths from the disease mounted, a multi-team dog sled relay was swiftly organized to transport 300,000 units of serum, which was already en route to Nenana by rail, the remaining 674 miles to Nome. On January 29th, Seppala and his team of 20 elite Siberians, with the ever-reliable Togo at the helm, bravely departed Nome to meet the westbound relay and retrieve the vital serum. Notably, Balto, another dog from Seppala’s kennel, was not chosen for this crucial initial leg, as Seppala felt he was not yet ready to lead.

Leonhard Seppala with six Siberian Huskies, including Togo on the far left, circa early 1920s

Leonhard Seppala with six Siberian Huskies, including Togo on the far left, circa early 1920s

With temperatures plummeting to -30 degrees Fahrenheit, Seppala and his dogs made astonishing progress on their dash east, covering over 170 miles in just three days. Unbeknownst to Seppala, the outbreak worsened in Nome, prompting officials to expand the relay with additional teams. In a daring move to save critical time and distance, Seppala steered his team across the treacherously frozen expanse of Norton Sound. Miraculously, amidst the vastness, Seppala ran directly into the team of Henry Ivanoff, one of the relay’s late additions, who was transporting the serum westward. The two teams narrowly avoided missing each other on the trail, but thanks to the acute senses of the dogs, the crucial connection was made. It then fell to Seppala and Togo to embark on the perilous return journey, bringing the serum closer to Nome.

The return trip across Norton Sound proved to be even more treacherous. The team became stranded on an unstable ice floe, surrounded by freezing water. With quick thinking and unwavering trust, Seppala tied a lead to Togo, his only hope, and hurled the dog across five feet of icy water towards the solid ice. Togo valiantly attempted to pull the floe supporting the sled, but the line snapped. In an astonishing display of intelligence and instinct, the once-in-a-lifetime lead dog retrieved the broken line from the frigid water, wrapped it around his shoulders like a harness, and single-handedly pulled his team to safety. This heroic act underscores the extraordinary bond and capabilities of Togo and Seppala.

After covering a near-impossible number of miles, Seppala and his team eventually completed their leg of the relay, handing off the serum in Golovin, just 78 miles from Nome. The final stretch of the relay included musher Gunnar Kaasen, who, against Seppala’s earlier assessment, had chosen Balto to lead his team. On February 3rd, 1925, Kaasen and Balto arrived in Nome to a hero’s welcome. The serum had reached its destination, and the town was saved from the grips of the epidemic.

The Enduring Legacy of Togo the Dog

While Gunnar Kaasen and Balto received the lion’s share of public glory for delivering the final leg, those intimately familiar with the “Great Race of Mercy” understood that Leonhard Seppala and Togo were the true heroes of the day. In the years following the historic serum run, Seppala embarked on tours across the Lower 48 states with his celebrated sled dogs. During one such trip to New England, Seppala’s smaller Siberian Huskies, led by Togo in what would be his final race, triumphed over a team of local Chinooks in a friendly competition, once again showcasing their superior endurance and speed.

Ultimately, Seppala and New England musher Elizabeth Ricker established a kennel of Siberians in Poland Spring, Maine. It was there that Togo, the indomitable dog, spent the remainder of his life in peace and dignity, passing away in 1929 at the age of 16. In 1932, Seppala returned to Alaska, and the kennel was entrusted to his friend Harry Wheeler. According to the Siberian Husky Club of America, all registered Siberian Huskies today can trace their ancestry back to the dogs from the Seppala-Ricker kennel or Harry Wheeler’s kennel, a profound testament to Togo’s enduring genetic legacy.

Seppala bidding farewell to Togo in Maine in 1929

Seppala bidding farewell to Togo in Maine in 1929

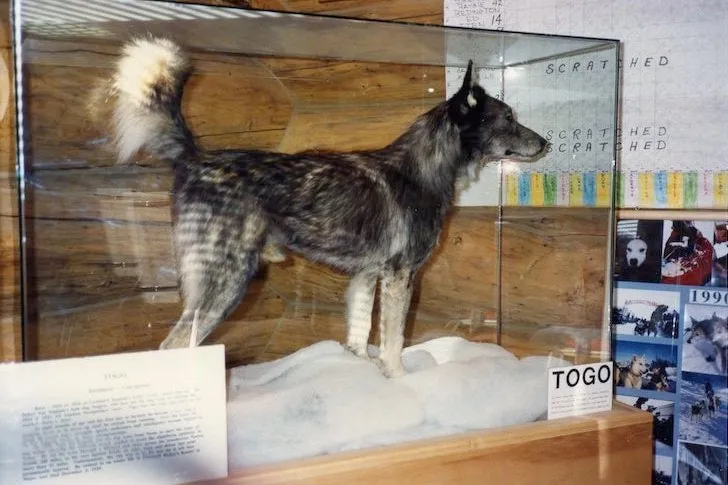

As decades passed, the historical record began to correct itself, and Togo gradually gained the recognition he truly deserved as the serum run’s ultimate hero dog. In 1983, his preserved body was given a place of honor at the Iditarod Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska. The modern Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, held annually in March, often traverses parts of the very same 1925 serum run trails, serving as a powerful reminder of the incredible feats accomplished by dogs like Togo. For an in-depth look at the famous sled dog movie true story that brought Togo’s journey to a wider audience, further resources are available. Additionally, for a comparison of the other renowned canine hero, consider delving deeper into the story of Balto the dog, and for insight into balto based on a true story.

Leonhard Seppala himself passed away in 1967 at the age of 89. A fitting tribute, the Leonhard Seppala Humanitarian Award is now presented annually to the Iditarod musher who exemplifies the best care for their dog team. Reflecting on Togo and the “Great Race of Mercy,” an event that irrevocably changed his own life and the sport of dog sledding, Seppala penned these poignant words in his unpublished autobiography: “Afterwards, I thought of the ice and the darkness and the terrible wind and the irony that men could build planes and ships. But when Nome needed life in little packages of serum, it took the dogs to bring it through.” His words encapsulate the profound truth of Togo’s heroism and the invaluable role sled dogs played in a moment of desperate human need.

Togo's mounted body at the Iditarod Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska

Togo's mounted body at the Iditarod Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska

The Story Of Togo The Dog is more than just a historical account; it is a testament to the extraordinary bond between humans and canines, and the incredible capabilities of our four-legged companions. Togo’s unwavering loyalty, exceptional endurance, and remarkable intelligence in the face of insurmountable odds serve as an enduring inspiration. He was not just a dog; he was a pivotal figure in a heroic endeavor, a true champion whose legacy continues to resonate with dog lovers and historians alike. His bravery ensured that hope reached Nome, cementing his place as one of the most remarkable animal heroes in history.

References & Further Reading On Togo:

- Leonhard Seppala: The Siberian Dog and The Golden Age of Sleddog Racing 1908-1941 by Bob & Pam Thomas

- The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against An Epidemic by Gay & Laney Salisbury

- Togo’s Fireside Reflections by Elizabeth M. Ricker