In the harsh winter of 1925, a deadly diphtheria outbreak gripped the isolated Alaskan port town of Nome, threatening its entire population, especially children. With the nearest life-saving antitoxin serum located an agonizing 674 miles away in Nenana, and extreme blizzards grounding all air travel, hope dwindled. The only viable option was a daring relay of sled dog teams, a desperate plea answered by the resilience of both humans and their canine companions. This extraordinary event, known as the “Great Race of Mercy,” saw 20 teams brave treacherous conditions to deliver the serum in an astonishing five and a half days. While Balto, the lead dog of the final 53-mile leg, famously became the face of this heroic endeavor, many historians and Alaskans in the know argue that the true unsung hero, whose unparalleled efforts saved countless lives, was Togo, led by the legendary musher Leonhard Seppala. Unearthing The Real Story Of Balto And Togo reveals a nuanced tale of sacrifice, endurance, and the remarkable bond between humans and animals in the face of overwhelming adversity.

The Race Against Death: Nome’s Desperate Plea

The year 1925 saw Nome, Alaska, a remote outpost nestled on the Bering Sea coast, face a grave public health crisis. A virulent strain of diphtheria began to spread rapidly, primarily affecting the community’s children. The town’s isolation meant medical supplies were scarce, and the only doctor, Curtis Welch, had limited antitoxin serum, which had also expired. A fresh supply was urgently needed, but getting it to Nome presented an almost insurmountable challenge. The serum was located in Anchorage and could only reach Nenana by rail. From Nenana to Nome, however, lay 674 miles of unforgiving Alaskan wilderness, deep snow, and deadly blizzards. Air travel, though considered, was quickly ruled out due to the extreme weather conditions and lack of suitable aircraft.

Thus, the monumental decision was made: a relay of powerful sled dog teams would carry the precious cargo across the vast, frozen expanse. Twenty teams and their mushers were assembled for this perilous journey. Among them was Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian-born musher widely regarded as Alaska’s most venerated and skilled dog driver, along with his extraordinary lead dog, Togo. While Balto would later capture public imagination for completing the final leg, it was Seppala and his twelve-year-old Siberian Husky, Togo, who covered the longest and most perilous stretch—an astounding 264 miles—compared to the average of 31 miles per team for the other participants. This incredible feat of endurance and navigation truly cemented Togo’s place as a pivotal figure in this historic event, a narrative sometimes overshadowed by the more publicized accounts of the real Balto dog.

Togo’s Ascent: From Undersized Pup to Sled Dog Phenomenon

Leonhard Seppala first arrived in Alaska in 1900, at a time when most sled dogs were the sturdy, burly Alaskan Malamutes or various mixed breeds. Working for the Pioneer Mining Company, Seppala quickly earned a reputation as one of Nome’s strongest and most capable mushers. Around this period, the first Siberian Huskies known in America were introduced to Nome by Russian fur trader William Goosak. These smaller, agile dogs, typically weighing around 50 pounds, defied expectations by securing third place in the annual All-Alaska Sweepstakes race in 1909, hinting at their impressive potential.

The following summer, English musher Fox Ramsay imported 60 of the finest Siberian specimens he could find, further establishing the breed’s presence in Nome. By the 1910 All-Alaska Sweepstakes, an all-Siberian team, expertly driven by musher “Iron Man” Johnson, clinched first place, setting a course record that stands to this day. It became increasingly clear that these “scrappy Siberians” possessed remarkable qualities as sled dogs, excelling in speed, endurance, and tenacity.

While precise whelping records from this era are scarce, it is widely accepted that Togo was born in Seppala’s kennel in 1913, the offspring of a dam named Dolly, now recognized as a foundational bitch in the Siberian Husky breed’s development. As a puppy, Togo was notably undersized and plagued by health issues, leading Seppala to initially deem him unfit for sled work. He even gave Togo away to a neighbor, believing the pup had no future as a working dog. However, Togo’s innate drive was undeniable; he soon flung himself through a glass window, escaping to return home. Seppala reluctantly accepted that he was “stuck” with the mischievous and incorrigible young dog.

As Togo matured, he became utterly captivated by the working sled dogs around him. Too young for a harness, he would often sneak away to run alongside teams training with Seppala, much to his owner’s frustration. His playful yet determined nature once led him to a dangerous encounter, resulting in a mauling after he ran up on a team of much larger Malamutes. Exasperated but perhaps also seeing a glimmer of the dog’s spirit, Seppala decided to harness the eight-month-old Togo and hook him into the team. Remarkably, Togo ran an astonishing 75 miles that day, quickly working his way into the lead position during his very first time in a harness. In an unexpected turn of events, Seppala had discovered the perfect lead dog he had always sought—a dog whose tenacity and intelligence would soon be put to the ultimate test.

The Unforgettable Odyssey: Togo’s Heroic Role in the 1925 Serum Run

Over the ensuing years, Togo’s legendary tenacity, unmatched strength, incredible endurance, and sharp intelligence became renowned across Alaska. As Seppala’s prized lead dog, Togo consistently guided his team through countless races and expeditions, both long and short. The bond between man and dog became unbreakable. During this period, Seppala himself solidified his reputation, winning the prestigious All-Alaska Sweepstakes in 1915, 1916, and 1917, often with Togo at the forefront.

By the time the diphtheria outbreak struck Nome in January 1925, Togo was 12 years old, and Seppala was 47. Both were arguably past their athletic primes. However, with the fate of Nome hanging precariously in the balance, the local authorities knew that this aging yet experienced duo represented their community’s last and best hope. As deaths from the rapidly spreading disease continued to mount, swift action became imperative. A multi-team dog sled relay was meticulously organized to transport 300,000 units of the vital antitoxin serum, which was already en route to Nenana by rail, across the remaining 674 miles to Nome.

On January 29th, Leonhard Seppala and his team of 20 elite Siberians, with the indomitable Togo faithfully leading the charge, set out from Nome. Their mission was to travel eastward, meet the westbound relay, and retrieve the life-saving serum. Notably, Balto, who would later achieve global fame, was not among Seppala’s initial selections, as the musher felt he was not yet prepared to lead such a critical team. Seppala believed in Togo’s unparalleled experience and leadership, qualities that would soon be tested beyond imagination.

Togo on a trail in 1921

Togo on a trail in 1921

Despite temperatures plummeting to -30 degrees Fahrenheit, Seppala and his dedicated dogs made astonishing progress in their eastward dash, covering more than 170 miles in just three days. All the while, the diphtheria crisis back in Nome intensified. Unbeknownst to Seppala, officials, desperate to accelerate the serum’s delivery, decided to add more teams to the relay. After making a perilous shortcut across the notoriously treacherous frozen expanse of Norton Sound—a move designed to save crucial time and distance—Seppala miraculously encountered the team of Henry Ivanoff, one of the relay’s newly added mushers, who was already transporting the serum westward. The two teams nearly missed each other amidst the swirling snow and vast landscape, but thanks in part to the keen senses of the dogs, the critical exchange was made. Naturally, the immense responsibility then fell back to Seppala and Togo to bring the serum back towards Nome, retracing a portion of their already arduous journey.

On the return trip across Norton Sound, the team faced another harrowing ordeal when they became stranded on a massive, unstable ice floe. With quick thinking, Seppala tied a lead to Togo, his only hope for rescue, and courageously tossed the dog across five feet of frigid water towards the more stable ice. Togo bravely attempted to pull the floe supporting the sled, but under the immense strain, the line snapped. In an astonishing display of intelligence and instinct, the once-in-a-lifetime lead dog had the presence of mind to snatch the broken line from the icy water, skillfully roll it around his shoulders like a makeshift harness, and eventually, with herculean effort, pull his team to safety. This incredible act of quick-thinking and bravery underscores why the true narratives of Balto real life movie and Togo often diverge in focus.

Leonhard Seppala with six of his Siberians

Leonhard Seppala with six of his Siberians

Back on solid land after covering an almost impossible number of miles, Seppala and his team finally made the critical serum handoff in Golovin, just 78 miles from Nome. The final stretch of the relay saw late additions, including musher Gunnar Kaasen, who, against Seppala’s own judgment regarding lead dog capability, had chosen Balto to lead his team. On February 3rd, 1925, Kaasen and Balto triumphantly rode into Nome to a hero’s welcome. The serum had arrived, and the town was saved from the grips of the epidemic, etching their names into history.

A Legacy Reimagined: Togo’s Enduring Impact

While Gunnar Kaasen and Balto were initially showered with much of the glory and public adoration, it was widely acknowledged by those who truly understood the intricacies of the serum run that Seppala and Togo were the real saviors of that fateful day. In the years following the historic event, Seppala embarked on trips to the Lower 48 states, showcasing his heroic sled dogs. During one memorable journey to New England, Seppala and his team, with Togo proudly leading in what would be his final race, took on a local team of much larger Chinooks. Despite their smaller stature, the nimble Siberians triumphed, a testament to Togo’s enduring spirit and leadership.

Ultimately, Seppala and New England musher Elizabeth Ricker decided to establish a kennel of Siberian Huskies in Poland Spring, Maine. It was there, amidst dignity and serenity, that the indomitable Togo lived out the remainder of his remarkable life. The legendary dog was finally laid to rest in 1929, at the venerable age of 16. In 1932, Seppala returned to Alaska, leading to the closure of the Poland Spring kennel, with the dogs being entrusted to his friend Harry Wheeler. According to the Siberian Husky Club of America, every registered Siberian Husky alive today can trace its ancestry directly back to the dogs from either the Seppala-Ricker kennel or Harry Wheeler’s kennel, underscoring Togo’s profound genetic legacy. The narrative of the Balto movie true story often omits this critical lineage and Togo’s broader influence.

Seppala with Togo in Maine in 1929

Seppala with Togo in Maine in 1929

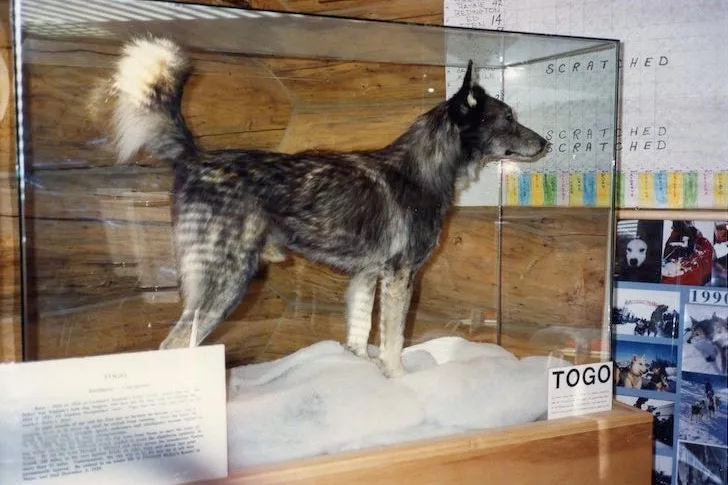

Over the decades, a growing number of historians and dog enthusiasts began to recognize Togo as the true hero dog of the 1925 serum run. His incredible mileage, strategic navigation through perilous terrain, and the dramatic rescue on the ice floe painted a picture of heroism that demanded recognition. Eventually, in 1983, Togo’s mounted body was given a place of honor at the Iditarod Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska, a fitting tribute to his indelible mark on sled dog history. The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, now the most famous among modern dog sled races, is held annually in March, with significant portions of its route traversing the very same historic trails taken during the 1925 serum run, forever linking Togo’s legacy to this ultimate test of endurance. This epic tale stands among the greatest dog stories ever told.

Seppala himself passed away in 1967 at the age of 89, leaving behind a profound legacy in the world of dog sledding. A fitting and enduring tribute, the Leonhard Seppala Humanitarian Award is presented annually to the Iditarod musher judged to have provided the best care for their dogs, embodying Seppala’s deep respect and love for his canine partners. Reflecting on Togo and the “Great Race of Mercy,” an event that irrevocably changed the course of his own life and the sport of dog sledding forevermore, Seppala eloquently summarized its profound significance in his unpublished autobiography before his passing:

“Afterwards, I thought of the ice and the darkness and the terrible wind and the irony that men could build planes and ships. But when Nome needed life in little packages of serum, it took the dogs to bring it through.”

Togo’s mount at the Iditarod Race Headquarters

Togo’s mount at the Iditarod Race Headquarters

Conclusion

The “Great Race of Mercy” stands as one of history’s most inspiring tales of animal heroism and human perseverance. While Balto deservedly received recognition for his crucial role in delivering the final leg of the serum, delving into the real story of Balto and Togo illuminates the immense, often understated contributions of Togo and his musher Leonhard Seppala. Their extraordinary journey—covering hundreds of miles of unforgiving terrain, navigating treacherous ice, and demonstrating unparalleled courage and intelligence—was a true testament to the spirit of the Siberian Husky and the unbreakable bond between musher and dog. Togo’s legacy extends far beyond a single heroic run, influencing the very genetics of the Siberian Husky breed and forever shaping the history of sled dog racing. His story reminds us that true heroism often unfolds quietly, fueled by unwavering dedication and an indomitable will to save lives.

References & Further Reading On Togo:

- Leonhard Seppala: The Siberian Dog and The Golden Age of Sleddog Racing 1908-1941 by Bob & Pam Thomas

- The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against An Epidemic by Gay & Laney Salisbury

- Togo’s Fireside Reflections by Elizabeth M. Ricker