The European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is a familiar sight in many urban and rural landscapes, known for its iridescent plumage and its tendency to gather in large flocks. These adaptable birds have successfully colonized much of North America, becoming a common presence around human settlements. Understanding their habitat, diet, nesting habits, and behavior provides insight into their ecological success and their interactions with native bird populations.

Habitat

European Starlings thrive in environments closely associated with human activity. They are commonly found in areas with mowed lawns, city streets, and agricultural fields, which provide ample foraging opportunities. For nesting, they seek out cavities in trees, buildings, and various man-made structures. Their primary needs include open, grassy areas for feeding, a reliable water source, and suitable cavities or niches for nesting. They tend to avoid extensive, unbroken forests, chaparral, and desert regions.

Food and Foraging

The European Starling is an opportunistic omnivore with a varied diet. Their primary food sources consist of insects and other invertebrates, which they actively search for in grassy areas. Their diet includes grasshoppers, beetles, flies, caterpillars, snails, earthworms, millipedes, and spiders. During certain seasons, they also consume a significant amount of fruit, favoring cherries, holly berries, hackberries, mulberries, and blackberries, among others. Additionally, they will eat grains, seeds, nectar, livestock feed, and readily scavenge from garbage.

Their foraging technique involves wandering over the ground in open areas with short vegetation. They are known to poke their closed bills into the ground and then use their strong jaw muscles to force the bill open, allowing them to probe for soil-dwelling insects and invertebrates. Starlings often forage alongside other species, including grackles, cowbirds, blackbirds, House Sparrows, Rock Pigeons, American Robins, and American Crows.

Nesting Behavior

Nest Placement and Description

Male European Starlings play a key role in nest site selection, using established sites to attract females. Nests are almost exclusively built within cavities. Common nesting locations include structures like buildings, streetlights, and traffic signal supports, as well as old woodpecker holes and nest boxes. Occasionally, they may nest in burrows or on cliffs. Nest holes are typically situated 10 to 25 feet above the ground, though they can be as high as 60 feet.

The nest construction process is relatively quick, with nests often completed in just 1 to 3 days. The male begins building the nest before mating, filling the cavity with a mixture of grass, pine needles, feathers, trash, cloth, and string. A depression is formed near the back of the cavity to house the cup-shaped nest, which is then lined with fine materials like feathers, soft bark, leaves, and grass. The female often makes final adjustments and may remove some of the materials added by the male. Throughout the nesting period, particularly during egg-laying and incubation, both sexes will add fresh green plants to the nest.

Nesting Facts

- Clutch Size: 3-6 eggs

- Number of Broods: 1-2 broods per year

- Egg Incubation Period: 12 days

- Nestling Period: 21-23 days

- Egg Description: Bluish or greenish-white.

- Hatchling Condition: Newly hatched starlings are altricial, meaning they are helpless and covered in sparse grayish down. Their eyes remain closed for the first 6-7 days, and they typically weigh around 6.4 grams at hatching.

Both the male and female participate in incubating the eggs.

Behavior and Social Interactions

European Starlings are highly gregarious and exhibit complex social behaviors, especially when in flocks. They communicate various signals to their conspecifics and other birds. Agitation can be signaled by flicking their wings or by staring intently at an opponent while adopting an erect posture, fluffing their feathers, and raising the feathers on their head. Submissive birds will crouch and move away with their feathers held sleekly against their bodies.

Confrontations can become aggressive, leading to birds charging at each other and using their long bills to stab. When perched together, starlings may displace each other by sidling along the perch until one runs out of space. Males attract females by singing near a chosen nest site and simultaneously flapping their wings in circular motions. After pairing, males exhibit strong mate guarding behavior, closely following their mates and aggressively chasing away other males.

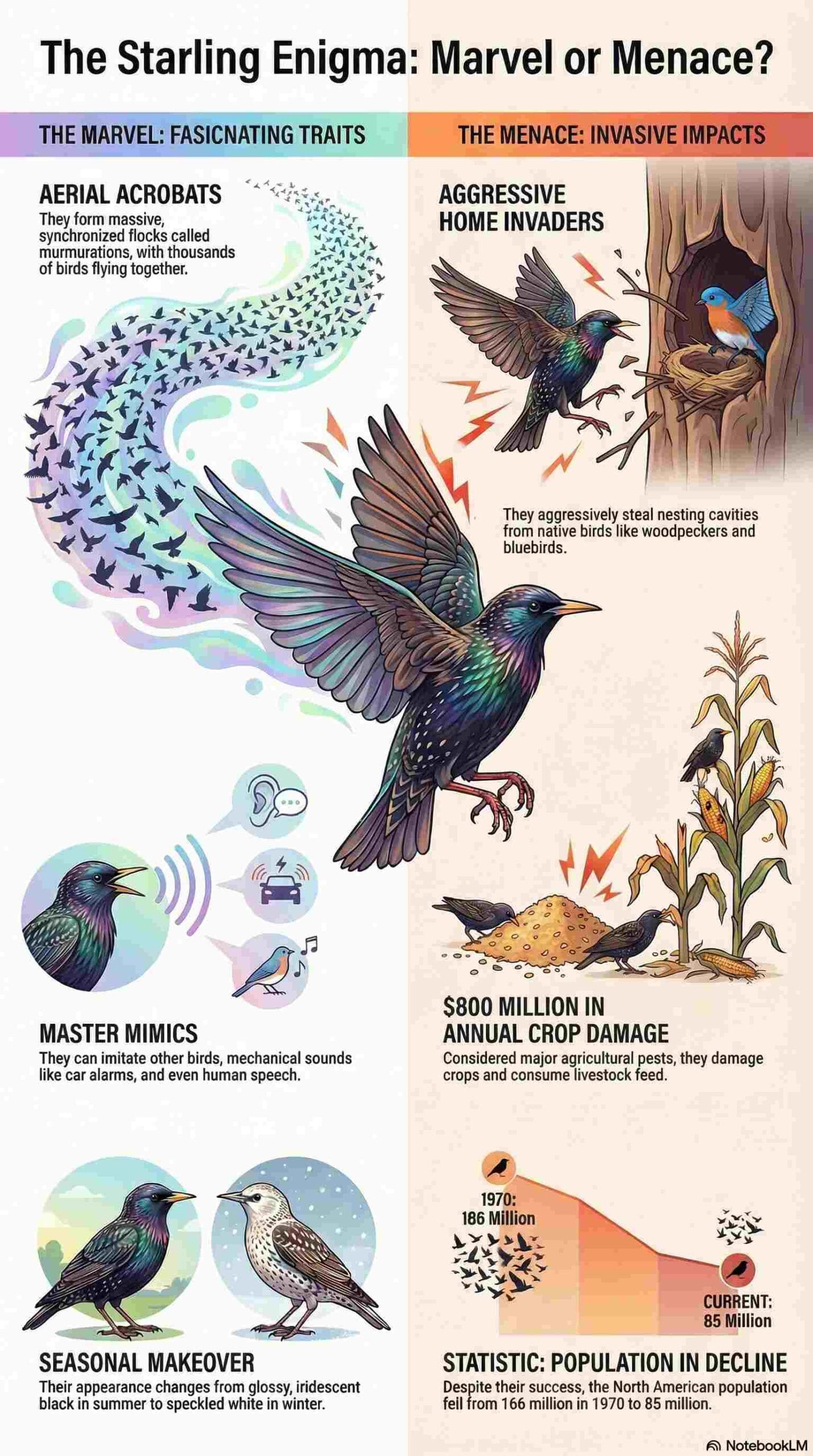

A notable aspect of their behavior is their aggressiveness towards other species, particularly when competing for nest sites. They are known to drive away native birds such as Wood Ducks, Buffleheads, Northern Flickers, Great Crested Flycatchers, Tree Swallows, and Eastern Bluebirds from desirable nesting locations.

Conservation Status

The European Starling is classified as common and widespread. However, data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey indicates a population decline of over 1.2% annually, resulting in a cumulative decrease of approximately 50% between 1966 and 2023. Partners in Flight estimates the global breeding population at 250 million and rates the species’ Continental Concern Score as 9 out of 20. A 2019 study estimated the European Starling population in the U.S. and Canada to be around 93 million.

As a successful introduced species in North America, European Starlings are fierce competitors for nest cavities and often displace native birds. Despite concerns about their impact on native populations, a 2003 study found minimal effects on 27 native North American species. While sapsuckers showed declines attributed to competition with European Starlings, most other native birds appeared to maintain stable populations in the presence of this introduced species.

References

Cabe, Paul R. (1993). European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Ehrlich, P. R., D. S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye (1988). The Birder’s Handbook. A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds, Including All Species That Regularly Breed North of Mexico. Simon and Schuster Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Kalmbach, E. R., and I. N. Gabrielson. (1921). Economic value of the starling in the United States. United States Department of Agriculture Bulletin No. 868, Washington, D.C.

Koenig, W. D. (2003). European Starlings and their effect on native cavity-nesting birds. Conservation Biology 17:1134–1140.

Lutmerding, J. A. and A. S. Love. (2020). Longevity records of North American birds. Version 2020. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Bird Banding Laboratory 2020.

Partners in Flight. (2020). Avian Conservation Assessment Database, version 2020.

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr and P. P. Marra. Decline of North American Avifauna. Science 366:120-124

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski Jr., K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link (2019). The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966–2019. Version 2.07.2019. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD, USA.

Sibley, D. A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds, second edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, USA.

Learn more at Birds of the World.