When your canine companion enjoys a romp in the park, a game of fetch, or even just a playful chase after a squirrel, they can sometimes suffer soft tissue injuries. These injuries, commonly known as sprains and strains, affect the muscles, tendons, and ligaments that support a dog’s joints and bones. While often used interchangeably, understanding the nuances between sprains and strains is crucial for proper care and recovery. This guide aims to provide comprehensive information for dog owners on recognizing, understanding, and managing these common orthopedic issues in their pets.

What Exactly Are Sprains and Strains in Dogs?

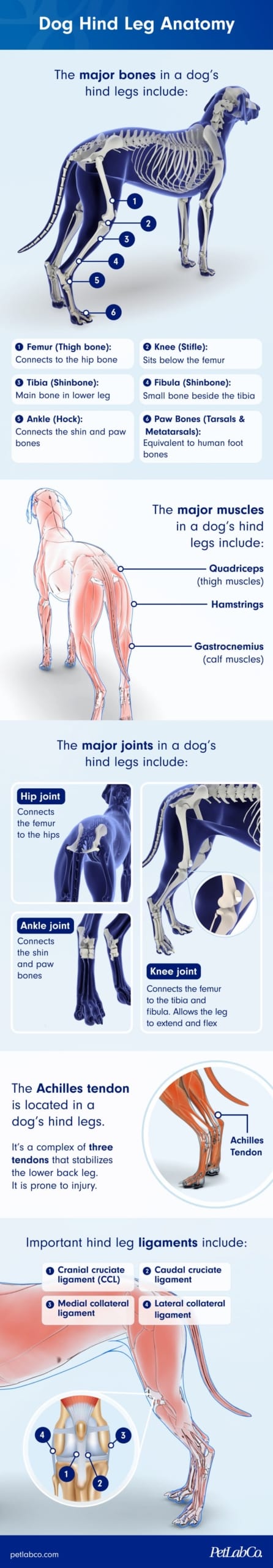

A dog’s musculoskeletal system is a complex network of bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments, much like our own. Injuries can occur during various activities, from running and jumping to simply misstepping. Soft tissue injuries, specifically sprains and strains, do not involve broken bones but rather damage to the connective tissues.

- Sprain: A sprain is an injury to a ligament, which are the strong, fibrous bands connecting bones to other bones at a joint. A sprain involves the stretching or tearing of these ligaments.

- Strain: A strain, on the other hand, affects a muscle or a tendon. Tendons are the connective tissues that attach muscles to bones. Strains involve the overstretching or tearing of muscle fibers or tendons.

A common human analogy is a sprained ankle, where the ligaments are damaged, making it painful to walk even though no bones are broken. Similarly, dogs may limp or favor an injured limb due to the pain and instability caused by these soft tissue injuries.

Common Types of Sprains and Strains in Dogs:

- Iliopsoas muscle strain: Affects the hip muscles.

- Supraspinatus tendinopathy: Injury to the shoulder tendon.

- Bicipital tendinopathy: Injury to the tendon in the upper front leg.

- Achilles tendon injury/avulsion (rupture): Damage to the tendon in the heel area.

- Carpal hyperextension: Injury to the ligaments in the dog’s “wrist.”

- Cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) injury: A common ligament tear in the knee, analogous to the ACL in humans.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Sprains and Strains

Observing your dog’s behavior is key to identifying a potential sprain or strain. Early detection leads to quicker intervention and better outcomes.

Key symptoms to watch for include:

- Lameness: This is the most obvious sign, where the dog avoids putting full weight on an affected leg.

- Difficulty with Movement: Hesitation when sitting down or getting up, or reluctance to jump on or off furniture.

- Decreased Activity: A noticeable reduction in their usual energy levels and enthusiasm for play.

- Pain and Discomfort: Whining, yelping, or general signs of distress, especially when the injured area is touched or moved.

- Stiffness: Particularly noticeable after periods of rest.

- Heat and Swelling: The injured area may feel warmer to the touch and appear visibly swollen compared to the opposite limb.

- Changes in Playing Habits: A reluctance to engage in play, chase toys, or roughhouse with other dogs.

Understanding the Causes of Sprains and Strains

These injuries typically result from minor trauma or overuse.

- Sprains often occur when a joint is twisted unnaturally, putting excessive force on the supporting ligaments. This can happen during sharp turns, landings from jumps, or stepping awkwardly.

- Strains are commonly caused by overexertion or sudden, forceful movements that overstretch muscles or tendons. High-impact activities such as agility training, intense play sessions, or even roughhousing with other dogs can lead to strains. A sudden dash to catch a moving object or an awkward jump off furniture can also be culprits.

Certain breeds and activity levels place dogs at higher risk. Highly athletic dogs participating in demanding sports are more prone to muscle strains. Additionally, large-breed dogs are more susceptible to CCL tears due to the biomechanics of their knee joints, which can experience increased force on the ligament.

Veterinary Diagnosis: How Your Vet Identifies Sprains and Strains

When you suspect your dog has a sprain or strain, a visit to the veterinarian is essential. The diagnostic process typically involves:

- Physical Examination: The veterinarian will closely observe your dog’s gait and watch how they move. They will gently manipulate the affected limb through various range-of-motion tests to identify pain, swelling, and any limitations in movement. For suspected CCL tears, a “cranial drawer” test may be performed to check for abnormal sliding within the knee joint.

- Radiographs (X-rays): X-rays are crucial for ruling out more serious conditions such as fractures, hip or elbow dysplasia, arthritis, bone cancer, or infections. They can also reveal secondary damage to the joint, such as bone spurs that may form as the body tries to stabilize an injured joint.

- Advanced Imaging: In some complex cases, especially in athletic dogs, diagnostics like ultrasonography, CT scans, or MRIs might be recommended. These may require referral to a veterinary orthopedic specialist.

Treatment Options for Sprains and Strains

Treatment depends on the severity and type of injury, ranging from conservative management to surgical intervention.

Conservative Treatment: Rest and Medication

Many mild to moderate sprains and strains can be managed effectively with:

- Rest: Strict rest is paramount. This means limiting activity to short, leash-walks for elimination purposes only. Running, jumping, and rough play must be avoided. Confining your dog to a crate or a small, safe area can help enforce rest.

- Pain Management: Veterinarians may prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) specifically formulated for dogs, such as Rimadyl, Metacam, or Galliprant. It is critical to never administer human NSAIDs to dogs, as they can cause severe gastrointestinal, kidney, and liver damage. Always follow your veterinarian’s dosage instructions precisely and report any side effects like vomiting, diarrhea, or loss of appetite.

- Cold Therapy: Applying a cold pack (wrapped in a towel) to the injured area for 5-10 minutes can help reduce swelling and pain, though this requires a cooperative patient.

- Physical Therapy: Once the initial pain and inflammation subside, your veterinarian may recommend a physical therapy plan to help restore range of motion and strength.

Surgical Intervention

More severe injuries, particularly complete ligament tears like CCL ruptures, often require surgery to restore stability and function.

- TPLO (Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy): Commonly performed on larger dogs, this procedure alters the angle of the knee joint to reduce stress on the reconstructed ligament. It is typically performed by an orthopedic surgeon.

- Lateral Suture: Often an option for smaller dogs, this surgery involves placing a strong suture material to stabilize the knee joint, acting as a new ligament. Many general practitioners can perform this surgery.

For dogs that are poor anesthetic candidates, specialized braces may be fitted to stabilize the joint externally, allowing scar tissue to form and provide some support over time.

Other Therapeutic Modalities

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT): Used in sports medicine to break down scar tissue in tendons.

- Cold Laser Therapy: Can help reduce inflammation and pain.

- Joint Supplements: Products containing glucosamine and chondroitin (like Dasuquin) may help support cartilage health and slow further joint degeneration.

- Adequan Injections: This medication provides building blocks for joint fluid, helping to lubricate joints and potentially slow cartilage breakdown.

Recovery and Long-Term Management

The recovery period varies significantly based on the injury and treatment method.

- Non-Surgical Cases: Typically require 2-4 weeks of strict rest, gradually returning to normal activity.

- Post-Surgical Recovery: Can range from 8-12 weeks, involving a carefully managed rehabilitation program.

During recovery, diligent adherence to activity restrictions is crucial. Pet parents must actively prevent their dogs from overexerting themselves, even if the dog seems eager to return to normal activities. Leash walking, crate rest, and sometimes even short-term sedation (prescribed by a vet, e.g., trazodone) may be necessary to ensure adequate rest and healing.

Preventing Sprains and Strains in Dogs

While not all injuries can be prevented, especially those with a genetic component, several proactive measures can reduce risk:

- Avoid Uneven Terrain: Be cautious when allowing your dog to run on unpredictable or unfamiliar surfaces.

- Monitor Exercise: Pay attention to your dog’s fatigue levels during exercise. Encourage breaks and slow down the pace if they show signs of exhaustion.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight is critical. Excess weight puts significant strain on joints, especially during activity.

- Conditioning: Avoid the “weekend warrior” syndrome. Dogs that are active throughout the week are generally better conditioned and less prone to injury than those with sedentary lifestyles followed by intense weekend activity. Regular, moderate exercise helps build muscle strength and joint stability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can my dog’s sprain heal on its own?

Many minor sprains can heal with rest and time. However, if your dog is not showing improvement within 10-14 days, or if lameness persists, veterinary assessment is necessary to rule out more serious issues and determine if additional treatment is required.

Can a dog walk on a sprained leg?

While a dog may be able to put some weight on a sprained leg, it is highly advisable to minimize activity. Leash walks should be kept brief and only for essential needs. Engaging in any form of running, jumping, or rough play should be strictly prohibited during the healing period. The goal is to prevent further injury and allow the damaged tissues to repair.