In the realm of biology, precisely identifying and classifying life forms is crucial for understanding their relationships and the intricate web of life on Earth. Two primary systems exist for naming organisms: scientific names and common names. While common names are familiar and rooted in everyday language, scientific names, with their Latin binomial structure, offer a universal and unambiguous method for classification. This distinction is vital for clear communication among scientists and for accurately documenting the diversity of life, from the majestic horse to the often-overlooked fungi.

The Precision of Scientific Names

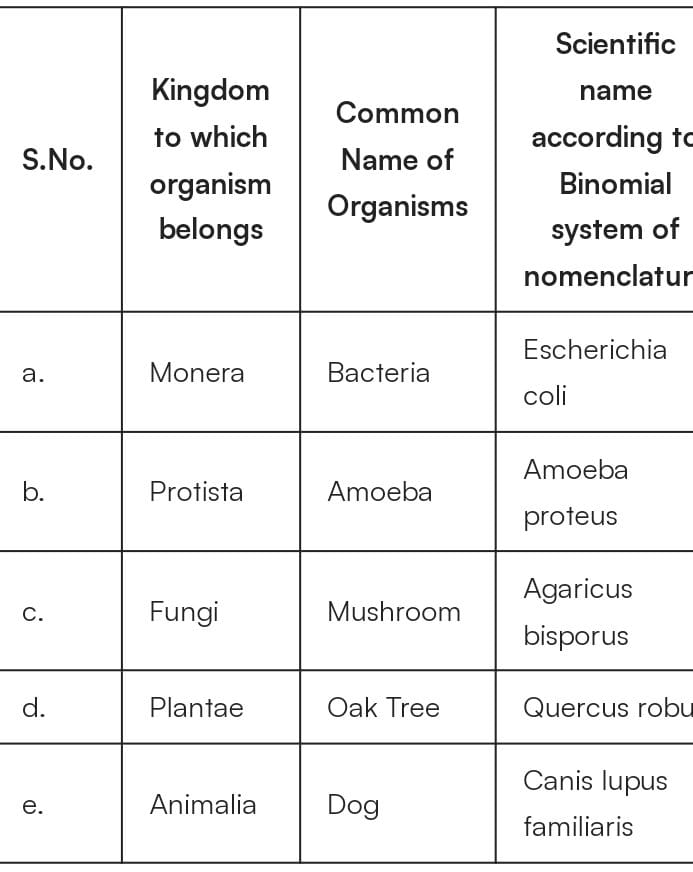

A scientific name is built upon a binomial system, comprising a genus name and a species epithet. For instance, the genus Equus encompasses horses and their closely related species. Within this genus, Equus burchellii refers to the plains zebra of Africa. The species epithet “burchellii,” when combined with the genus Equus, distinctly identifies the zebra, differentiating it from other members of the Equus genus. This hierarchical system of scientific nomenclature, as outlined by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, organizes life into ascending ranks, starting with kingdoms. These ranks reflect biological and evolutionary relationships, ensuring that organisms within a group share fundamental similarities. For example, all species within the fungus genus Puccinia are plant rusts, a type of parasite that thrives on living plants. Genera are further grouped into families, such as the Pucciniaceae family, to which Puccinia belongs. Members of this family, while potentially showing more variety, fundamentally represent the same kind of organism – in this case, plant parasites.

The Familiarity of Common Names

Common names are those bestowed upon organisms in the language of the people who interact with them. For example, “horse,” “cheval” (French), “el caballo” (Spanish), and “Pferd” (German) are all common names for the creature scientifically known as Equus caballus. Even variations in a horse’s coat color, such as the “Pinto” designation for horses with white patches on a darker coat, do not alter its scientific classification as Equus caballus. This is because color is not considered a “diagnostic characteristic” in scientific classification. Diagnostic characteristics are the defining features that distinguish one species from all others. While an organism may have numerous common names across different languages and regions, it possesses only one unique scientific name, universally recognized and written in Latin. This scientific name is exclusively used once in the scientific community to identify a particular organism, ensuring clarity and preventing duplication.

The Indispensable Role of Both Systems

The existence of both common and scientific names serves distinct but complementary purposes. Firstly, not all organisms possess a common name. Many species, particularly fungi living unnoticed in the soil or those lacking immediate economic importance or edibility, may never acquire a common name. However, all such organisms are assigned scientific names. The scientific naming system, unlike common names, is regulated to prevent duplication. The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature enforces the creation of a single “valid name” through a formal process that includes a Latin description of the organism. Common names, on the other hand, can draw from mythology, local history, or simply descriptive physical properties. For instance, the fungus genus Geastrum, derived from the Latin words for “earth” and “star,” is commonly known as “earthstar.”

Despite their uniqueness, scientific names are not immutable. As scientific research methods advance, providing deeper insights into a species’ evolutionary relationships, its scientific name may be revised to reflect this enhanced understanding. This could involve reclassifying the fungus into a different genus or family. Historically, the transition from visual examination with the naked eye to the use of microscopes for studying spores led to significant name changes. More recently, advancements like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for highly detailed spore imaging and DNA analysis have further refined our ability to assign names that accurately represent biological relationships.