The genetic landscape of horse breeds is a testament to evolutionary forces, shaped by both natural and artificial selection that have sculpted unique genomic features within each breed. The advent of high-throughput genotyping technologies has revolutionized our ability to explore this genetic variation on a genome-wide scale, enabling the identification of genomic regions exhibiting divergent selection between distinct breeds and even among different horse types sharing similar phenotypic characteristics.

This study delves into the genetic differentiation of six Polish horse breeds: Arabian, Małopolski, Hucul, Polish Konik, Sokolski, and Sztumski. These breeds were categorized into three major types: light, draft, and primitive horses, each selected based on criteria such as utility, exterior appearance, performance, size, and coat color. By employing the population differentiation index (FST), a commonly used metric for assessing variations in locus-specific allele frequencies between populations, we aimed to detect signatures of selection within these breeds.

Our analysis uncovered several genomic regions and associated genes that are potentially crucial for breed phenotypic differentiation. These include genes linked to energy homeostasis during physical exertion, heart function, fertility, disease resistance, and motor coordination. Notably, we confirmed previously identified associations of loci on Equus caballus chromosome 3 (ECA3), spanning the LCORL and NCAPG genes, with the regulation of body size in our draft and primitive (small-sized) horses. Furthermore, the efficacy of the FST-based approach was validated by the robust selection signal detected in the blue dun colored Polish Konik horses at the TBX3 gene locus, a gene previously implicated in dun coat color dilution in other horse breeds.

The findings of this study underscore the power of FST-based methods in identifying diversifying selection signatures within analyzed horse breeds, particularly highlighting pronounced signals at loci responsible for fixed, breed-specific features. While this research proposes several candidate genes under selection that may explain observed genetic diversity, further functional and comparative studies are essential to confirm and elucidate their precise effects on these horse breeds.

Introduction to Horse Breed Differentiation

The remarkable diversity in phenotypes observed in the current horse population is largely a consequence of selective breeding aimed at enhancing specific traits. Since domestication, various selection criteria—focused on improving horses for transportation, agriculture, and horsemanship—have been applied. This has led to the specialization of particular populations, ultimately resulting in the establishment of formal breeds. These breeds often exist as largely closed populations, characterized by high genetic uniformity among individuals within the breed. Contemporary selection practices in most horse breeds primarily target improvements in appearance and performance. However, alongside highly specialized breeds, certain horse populations are valued for their primitive characteristics, demonstrating a robust constitution suited for survival in less managed conditions. While natural selection played a role in shaping these populations, selective breeding for breed standards and mating within closed populations mean their genetic characteristics often parallel those found in other horse breeds.

Both natural and artificial selection induce shifts in allele frequencies between populations, leading to the fixation of different variants and haplotype structures within separate breeds over time. Various statistical concepts and methods have been employed to detect these selection signatures from genome-wide SNP data in livestock. Some methods focus on within-breed genomic characteristics, while others rely on inter-breed genetic variation. Most available techniques are based on: (i) the high frequency of derived alleles and other consequences of hitchhiking within a population; (ii) the length and structure of haplotypes, quantified by extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH) or related statistics; and (iii) the genetic differentiation between populations, measured by FST or similar statistics. The genetic differences arising from selection are presumed to be concentrated at functional variant loci beneficial for the selected traits. Through linkage disequilibrium across the genome, the approximate location of these functional variants can be identified using neutral genome-wide SNP panels and comparative analysis of allele frequency distributions across different breeds. A widely adopted approach for detecting diversifying selection signatures involves measuring population differentiation based on locus-specific allele frequency variations between populations, quantified by the FST statistic. This statistic is often averaged over specific chromosome distances to account for stochasticity. FST offers insights into genomic variation at a locus among populations relative to variation within populations. These inter-breed differences, indicative of diversifying selection, have been successfully used to map genomic loci containing genes responsible for various phenotypic traits in diverse species, including coat color, size, muscling, production, and reproduction [10–14]. The identification of selection signals across the genome, coupled with a candidate gene approach, has also proven valuable in detecting loci associated with size, performance, coat color, and gait in several horse breeds.

To expand our understanding in this field and provide more data on candidate gene loci underlying important breed-specific features, this study aims to identify selection signatures by analyzing the genetic diversity of six distinct horse breeds. These breeds represent three major categories: light, draft, and small-sized primitive horses. Among the light horses, besides the well-known Arabian, we analyzed the Małopolski horse, a balanced riding horse developed primarily from a native Polish population crossed with Thoroughbreds and Arabians. The primitive breeds included the Hucul and the Polish Konik. Both are small-sized horses exhibiting characteristics of feral populations. Hucul horses, originating from the Carpathian Mountains, are likely descendants of various horse types, including Tatar, Oriental, Arabian, Turkish, and Przewalski’s horses, as well as those with Norse blood. The Polish Konik is believed to have descended from the now-extinct Tarpan horse of the native Polish population and is characterized by primitive features such as a mouse-dun coat color and a dorsal stripe. The draft horses analyzed were the Sokolski and Sztumski breeds. The Sokolski horse resulted from crossbreeding local Polish mares of Polish Coldblood type with imported Ardennais and Breton sires. The Sztumski horse is the largest and heaviest of the cold-blooded horses in Poland, originally developed from a local population crossbred mainly with Ardennes and Belgian sires. Direct comparisons between these horse types and breeds can reveal candidate gene loci potentially responsible for constitution, size, and coat color, thereby contributing to the understanding of the genetic background and sources of variation in horse phenotypic features. Notably, five of the six breeds analyzed are part of conservation programs adhering to FAO National Rare Livestock Breeds Preservation guidelines. To our knowledge, these native horse breeds had not been previously studied in terms of diversifying selection, making this study a novel contribution to understanding horse breed genetic diversity and variation.

Methods and Materials

Animal Samples and Genotyping

This research utilized blood samples from 571 horses (both males and females) randomly selected from various herds across six different breeds. The chosen breeds represent three major horse types: light horses—Arabian (n = 124; AR) and Małopolski horse (n = 56; MLP); primitive horses—Hucul (n = 116; HC) and Polish Konik (n = 99; KN) breeds; and draft horses—Sokolski (n = 107; SOK) and Sztumski (n = 69; SZTUM). Blood was collected from the jugular vein by a veterinarian into EDTA K3 tubes. Samples from Arabian horses were sourced from three studs: SK Janów, SK Michałów, and SK Białka, which were project partners. For Małopolski horses, samples were collected from these studs and from individual breeders with their explicit consent. Biological material from Hucul horses was obtained from the Gładyszów Stud and ZDIZ PIB Odrzechowa, with the approval of their respective Chairmen. Polish Konik samples were collected from the Popielno Research Station, IRiŻZ PAN, and the Kalitnik—PTOP Research Station, with the consent of the Presidents. Biological material from draft horses was collected from herds involved in conservation programs for Sztumski and Sokolski horses, located in the Podlasie (Sokólski) and Pomorskie (Sztumski) provinces. Participating farmers signed cooperation agreements with the National Research Institute of Animal Production (NRIAP), committing to provide data and biological material for research. Breeders involved in conservation programs are obligated to maintain animals according to animal welfare standards, overseen by district veterinarians. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples using a Sherlock AX kit (A&A Biotechnology). Following quality control, samples were genotyped using the Neogen Equine Community BeadChip assay (Illumina) following the standard Infinium Ultra protocol. All animal procedures were approved by the Local Animal Care Ethics Committee No. II in Kraków (permission number 1293/2016), in compliance with EU regulations.

Data Filtering

The Neogen Equine Community array (Illumina) was used for genotyping, providing probes for 65,157 SNPs with an average inter-marker distance of 36.3 kb. Genotypes with a call rate greater than 0.97 were retained for analysis. The initial SNP set was filtered to exclude markers on sex chromosomes (based on the EquCab2.0 genome build). The preliminary filtered SNP panel comprised 61,268 markers. Further reduction occurred through population-wide filters, including a minor allele frequency (MAF) threshold of 5% and exclusion of SNPs with more than 20% missing genotypes across the entire population. Additionally, SNPs with a critical p-value for Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) less than 1.0E-06 in each breed individually were removed. This process resulted in a final SNP panel of 52,023 markers, distributed across the genome with an average inter-marker distance of 43.0 kb.

Identification of Diversifying Selection Signatures

Genomic regions with differentially fixed variants or significant allele frequency differences between distinct breeds were identified using pairwise Wright’s FST, a standard measure of population genetic differentiation. The FST values obtained for each SNP in pairwise comparisons were standardized by breed according to the methodology proposed by Akey et al.. Standardized FST values (di) were calculated as: di = (FST – expected FST) / standard deviation of FST, where expected FST represents the expected value and standard deviation of FST between breeds i and j, calculated from all analyzed SNPs. To account for random locus-by-locus variation, a 10-SNP sliding window was applied to the computed di values. Regions identified as potentially affected by diversifying selection were defined as those falling within the 99.9th percentile of the empirical distributions of window-averaged di values. Overlapping regions under selection were merged. For the purpose of identifying potentially linked genes, these regions were extended by 25 kb on both ends. Additional comparisons using di values were conducted between major horse types (light, primitive, and draft) to detect potential selection differences among them. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype block structure within the most diversified regions among the studied breeds were analyzed using Haploview 4.2 software. This analysis examined pairwise LD over distances up to 500 kb and identified blocks using a method proposed by Gabriel et al.. Furthermore, detailed analyses were performed for previously identified candidate gene loci associated with horse body size (LCORL/NCAPG) and the dun coat color phenotype (TBX3).

Visualization of population differentiation was achieved through principal component analysis (PCA) of SNP genotypes and a cladogram constructed based on weighted FST distances using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method. Functional annotation of genes located within the strongest selection signals was performed using the KOBAS 3.0 web server and the Panther Classification System. Gene list enrichment analysis was conducted using all known horse genes (genome-wide) with a correction for multiple testing.

Results

SNP Panel Statistics and General Genetic Differentiation

The data filtering process yielded a common set of 52,023 polymorphic SNPs (MAF > 0.01) across the entire population, with an average inter-marker distance of 43.0 kb (±45.1). The number of polymorphic SNPs per breed varied, ranging from 47,495 in Hucul (HC) to 50,775 in Małopolski (MLP) horses. The average MAF across all SNPs was lowest in Polish Konik (KN) at 0.214 and highest in MLP at 0.262. Observed heterozygosity per breed averaged between 0.296 in KN and 0.353 in MLP (Table 1). Mean and weighted overall pairwise FST distances were lowest between the two draft horse breeds (0.012 and 0.014, respectively). The highest level of genetic differentiation was observed between Arabian horses and the primitive or draft breeds (Table 2).

Breed differentiation was further visualized using PCA based on SNP genotypes and an FST-based cladogram generated via the NJ method (Fig 1). The PCA clearly separated the genetic profiles of the light horses from the other breeds, and the Hucul horses exhibited a distinct genetic profile. The NJ method revealed similarities in genetic profiles within major horse types, with the exception of the primitive horses, which were clearly distinct (Fig 1).

Breed-Specific Selection Signatures

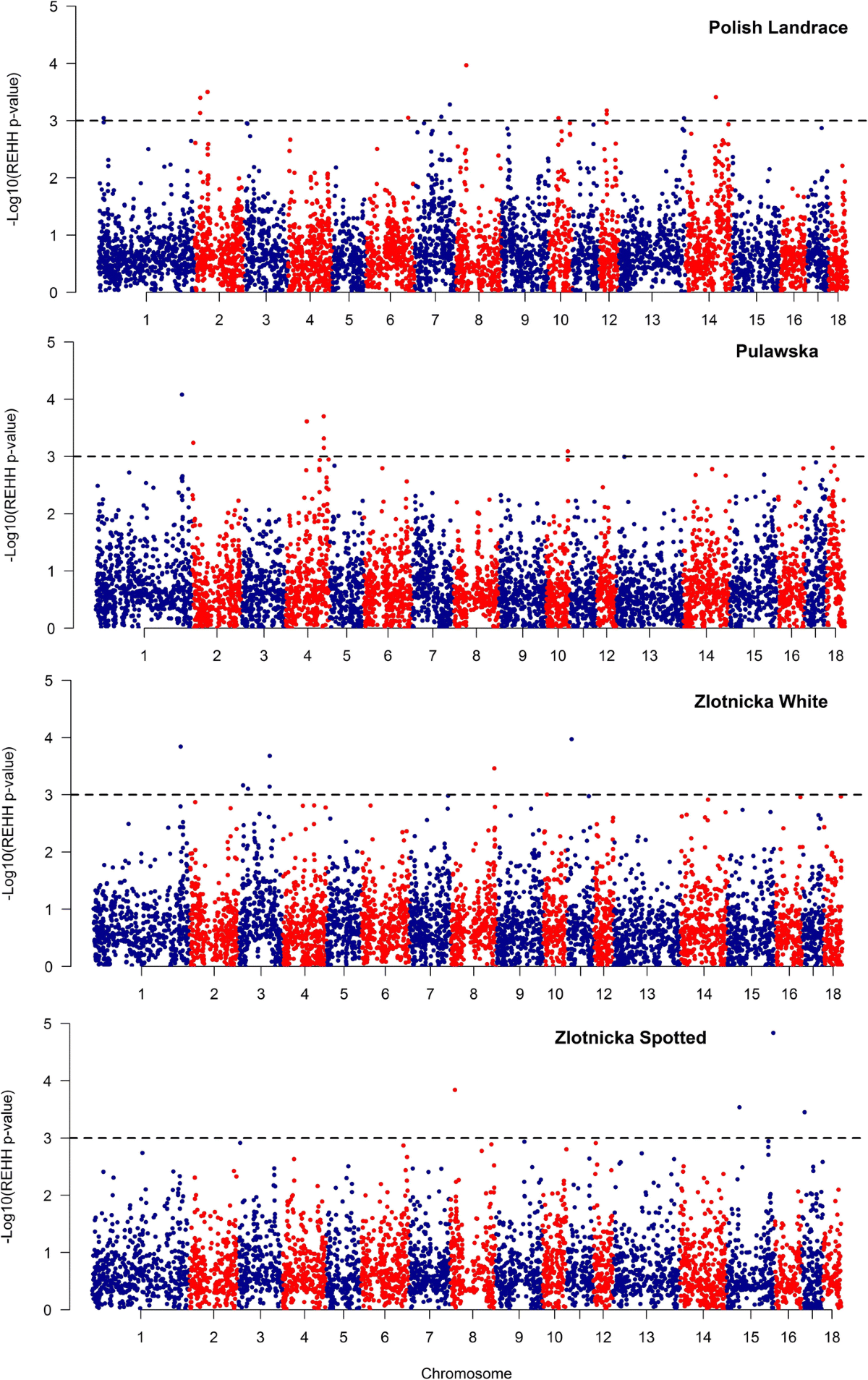

Signatures of diversifying selection among the studied horse breeds were identified using breed-normalized pairwise FST distances (di) (Supplementary File 1). Following smoothing of the di values using a moving average, the top 0.1% of observations were considered indicative of the most pronounced selection signals associated with breed-specific traits. Merging overlapping regions revealed 10 (for MLP, SOK) to 15 (for KN) genomic loci with strong selection signals per breed, ranging in size from 163.9 kb to 4.4 Mb (Table 3). The highest number of strong selection signals across all breeds were detected on ECA1 and ECA11, with only a few regions identified on ECA12, 14, 16, 19, 21, and 24. Several genomic regions with strong selection signals overlapped between different breeds, located on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 11, 15, and 22 (Table 3, Fig 2). The most frequently observed selection signal, common to Hucul (HC), Polish Konik (KP), Sokolski (SOK), and Sztumski (SZTUM) breeds, was located on ECA11 between 22.9 and 23.7 Mb.

To analyze the gene content within the genomic regions exhibiting the strongest selection signals (top 0.1% of di values), each region was expanded by 25 kb upstream and downstream to include potentially linked genes. This process identified 65 (SOK) to 169 (MLP) ENSEMBL genes per breed (Supplementary File 2). Analysis of genes common across different breeds revealed that 18 genes were shared among HC, KP, SOK, and SZTUM breeds, while no common genes were found between MLP and both the primitive and draft horses (Supplementary File 3). Functional classification of well-annotated genes using Panther software based on Gene Ontology (GO) terms indicated that all detected genes across breeds (506 unique genes) were predominantly involved in cellular processes (32% of genes), such as cell communication and cell cycle, or metabolic processes (22%), including primary metabolic processes (89 genes), nitrogen compound metabolic processes (50 genes), and phosphate-cogitating compound associated processes (28 genes). These genes were linked to numerous Panther pathways, with the highest number associated with inflammation mediated by chemokines and cytokines (8 genes), and TRH receptor signaling, TGF-beta signaling, CCRK signaling map, or GRH receptor signaling pathways (5 genes each).

Functional classification performed on individual breeds revealed distinct differences in enriched GO categories (Supplementary File 4). Pathway analysis of genes found in Arabian horses highlighted genes associated with ATP synthesis coupled electron transport (COX4I1), bile secretion (ABCG8, ABCG5, ADCY1), fat digestion, oocyte meiosis (ADCY1, ANAPC7), ovarian steroidogenesis (ADCY1), and insulin signaling (CBLB) or secretion (ADCY1) pathways. Genes identified in Małopolski horses were linked to largely similar biological pathways as those in Arabian horses, including progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation (PRKACA, ANAPC5, ANAPC7), oocyte meiosis (PRKACA, ANAPC5, ANAPC7), fatty acid metabolism (TECR), and processes related to the immune system, such as leukocyte transendothelial migration (MYL2) and antigen processing and presentation (PRKACA), as well as inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels (PRKACA, PRKCD). Within the selection signatures characteristic of the primitive Hucul breed, several genes involved in processes like olfactory transduction (LOC100066263, LOC100066541, LOC100055475, LOC100066487, LOC100060476, LOC100060509, LOC100066238), cardiac muscle contraction (ACTC1), and alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism (GFPT2, CPS1) were found. Among the 100 genes detected in the strongest selection signatures in Polish Konik horses, genes associated with inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels or T cell receptor signaling pathway (PLCG1), chemokine signaling pathway (GNG4), and glycerolipid metabolism (LPIN3) were identified. Genes identified in the draft Sokolski horses were linked to cardiac muscle contraction (ATP1A1, CACNB1), bile secretion (ATP1A1, ABCG8), fat digestion/absorption (ABCG8), and insulin secretion (ATP1A1), pathways largely similar to those found in light horses. Genes associated with diversifying selection signatures in the Sztumski horse included those involved in the prolactin signaling pathway (CWC25), cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (LASP1), or general metabolism (PCGF2) (Supplementary File 5).

Signatures of Diversifying Selection Between Major Horse Types

To identify genomic regions with differentially fixed variants among major horse types, di values were calculated between pairs of breeds categorized as light (AR, MLP), primitive (HC, KN), and draft (SOK, SZTUM). The resulting di values were smoothed using a 10-SNP sliding window, and the top 0.1% of observations were analyzed for gene content (Supplementary File 6).

This comparison revealed 14 genomic regions with significant allele frequency differences between light and draft horses, 11 regions between light and primitive horses, and 9 regions between primitive and draft breeds. The highest number of such divergently selected regions was identified on ECA2 (6 regions), ECA8 (4 regions), and ECA22 (4 regions). The size of individual regions ranged from 124.2 kb to 1.1 Mb. Regions overlapping between at least two different comparisons were found on ECA2, 4, 8, and 19, primarily occurring in comparisons involving light horses and the other two types (Table 4, Fig 3). Analysis of selection signature plots indicated similar patterns of allele frequency differences between light horses and the two other types, and a distinct pattern of frequency differences between primitive and draft horses (Fig 3).

Within the identified selection signatures for major horse types, a total of 220 unique genes were detected—ranging from 77 to 87 for separate comparisons (Supplementary File 7). Genes with differentially fixed variants between light and draft horses were associated with several biological pathways, most notably those related to progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation and oocyte meiosis (ANAPC5, ANAPC7, ADCY1), cardiac muscle contraction (MYL2, ATP1A1), adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes (ADCY1, MYL2, ATP1A1), salivary or bile secretion, insulin secretion, and thyroid hormone synthesis (ADCY1, ATP1A1). These genes were also linked to biological processes responsible for energy homeostasis, such as ATPase activity or mitochondrial inner membrane function (ATP5F1E) (Supplementary File 8).

Regions with differentially fixed variants between primitive and light horses encompassed 77 genes associated with various biological pathways, with the most enriched being those related to immune system functions (e.g., HTLV-I infection, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, bacterial invasion of epithelial cells) and reproduction (oocyte maturation and oocyte meiosis) (ANAPC7, ADCY1). These genes were also involved in biological processes related to lactate transmembrane transport (SLC16A1), pyridine-containing compound metabolic processes (NMNAT1), and wound healing (RHOA) (Supplementary File 8).

Genomic regions differentiating primitive and draft horses contained 87 distinct genes, including those associated with the Ras signaling pathway (GNG4, FGF10), sulfur relay system (NFS1), MAPK signaling pathway (CACNB1, FGF10), cardiac muscle contraction (CACNB1), and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (GGPS1). These genes were also annotated to a wide range of biological processes, including keratinocyte differentiation, angiogenesis, and bone development (MED1) (Supplementary File 8).

Particular attention was paid to genes located within the strongest signals of diversifying selection between different horse types, and an analysis of the most divergently selected regions per comparison was conducted. For the comparison between draft and light horses, a region on ECA7 (39.8–40.8 Mb) was analyzed. For the comparison between primitive and light horses, a region on ECA8 (20.8–21.5 Mb) was examined. For the comparison between draft and primitive horses, a region on ECA11 (22.8–23.9 Mb) was investigated (Fig 3). Additionally, linkage disequilibrium and haplotype block structure were established for these regions to identify potentially selected haplotypes.

Within the region on ECA7 (39.8–40.8 Mb), aside from two pseudogenes and one uncharacterized protein-coding gene, two genes (NTM, encoding Neurotrimin, and OPCML, encoding opioid-binding protein) involved in central nervous system functioning were identified. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype structure analysis at this locus revealed two haplotype blocks with common haplotypes exhibiting a frequency above 0.7 in all analyzed breeds (Supplementary File 9). This region also neighbored a large chromosomal area with high LD in Arabian (AR) and Małopolski (MLP) horses, located upstream of the analyzed selection signature (40.1–52.5 Mb).

In-depth analysis of the locus on ECA 8 (20.8–21.5 Mb) identified 14 genes within the regions, including one uncharacterized protein. The remaining genes included: MYL2, CCDC63, PPP1CC, HVCN1, TCTN1, PPTC7, RAD9B, VPS29, FAM216A, GPN3, ARPC3, ANAPC7, and ATP2A2. LD analysis at the ECA8 locus indicated moderate linkage and an unambiguous haplotype block structure, although some overlapping haplotype blocks with frequencies higher than 0.5 were found for three out of the four compared breeds (Supplementary File 10).

Within the extensive region on ECA11 (22.8–23.9 Mb), exhibiting the highest allele frequency differences between draft and small-sized primitive horses, 30 different genes were detected (including two pseudogenes and five uncharacterized proteins). One of these, the LASP1 gene, was previously proposed as a candidate gene for size in horses. However, the LD structure analysis at this locus showed a relatively rapid decay and a haplotype block structure that was difficult to associate with the selection signal (Fig 4). Nevertheless, overlapping haplotype blocks were detected in the draft horses, spanning haplotypes with frequencies exceeding 0.7.

Diversifying Selection Signatures at Candidate Gene Loci for Size and Coat Color Dilution

In prior studies, the ECA3 locus, encompassing the LCORL and NCAPG genes, was shown to be differentially selected between several draft and miniature Horse Breeds And was identified as explaining a significant portion of the genetic variance for size in an across-breed study. In our findings, one of the four strongest diversifying selection signals detected between the small-sized primitive horses and draft horses encompassed this previously described locus on ECA3 (104.8–105.9 Mb), which includes both genes. Haplotype structure analysis at the locus revealed overlapping haplotype blocks for three of the analyzed breeds (KP, HC, SOK); however, these spanned a neighboring pseudogene locus rather than the LCORL/NCAPG positions (Fig 5). This observation might relate to the potential location of functional variants in the upstream region of LCORL (as NCAPG is transcribed in the opposite direction), possibly influencing its promoter activity.

Another locus subjected to detailed analysis was a genomic region on ECA8 spanning the TBX3 gene. Previous research indicated that the dun phenotype, characteristic of the Polish Konik horse, is associated with mutations in the TBX3 gene. Our analysis of diversifying selection signatures specific to individual breeds identified a strong selection signal in the Polish Konik that directly overlapped with this locus (ECA8: 17.9–18.6 Mb). At this locus, low levels of LD and a poor haplotype structure were observed. However, the detected di signal closely matched the genomic position of TBX3 (Fig 6).

Discussion

This study employed a genome-wide scan for diversifying selection signatures in horse breeds selected for performance, exterior, and size. We included primitive, extensively selected horses with well-developed characteristics such as robust fertility, disease resistance, and adaptation to harsh environmental conditions as comparative populations. Numerous genomic regions exhibited divergent selection between specific breeds, along with selection signatures characteristic of particular horse types (light, draft, and primitive). This enabled the identification of several candidate genes and associated metabolic pathways potentially responsible for the divergent phenotypes observed across the studied breeds. To facilitate a comprehensive analysis of the results, we focused on genomic regions with the strongest selection signals, presumed to be near fixation within specific breeds and encompassing variants responsible for well-established (fixed) breed-specific traits. To manage the complexity of the numerous genes found within these selection signals, we performed pathway analysis to identify enriched processes. Given that the detected selection signatures are linked to a variety of phenotypic features differentiating the breeds—features governed by complex molecular mechanisms—we anticipated only a few genes associated with distinct biological processes in the enrichment analysis. Nonetheless, this analysis effectively reduced data complexity, allowing us to identify pathways and underlying genes potentially targeted by diversifying selection.

The highest number of strong diversifying selection signals across all breeds was detected on ECA1 and ECA11. These autosomes were previously implicated in loci affecting size in horses, identified through both population genetics and quantitative genomics methods. Several genomic regions with strong selection signals overlapped between different breeds, located on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 11, 15, and 22 (Table 3, Fig 2). The most consistently observed selection signal, common to multiple breeds, was found on ECA11 between 22.9 and 23.7 Mb. This region was previously shown to overlap with the LASP1 gene locus, which has a presumed influence on growth and body size traits.

Analysis of linkage disequilibrium at the most prominent selection signals on ECA7, 8, and 11 between major horse types revealed relatively low LD levels and a poorly conserved haplotype structure across the analyzed breeds. This suggests that the variants selected in these regions are evolutionarily ancient and their frequencies increased during breed formation, rather than being solely driven by recent selection. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that high LD, typically expected in regions with variants under strong ongoing positive selection, actually decayed at the analyzed loci due to meiotic recombination over multiple generations. This aligns with the notion that alternative statistical methods, such as extended haplotype homozygosity tests, may be more adept at detecting selection signatures associated with ongoing selection targeting novel functional variants. Nevertheless, selection signals linked to variants not yet fully fixed within the studied populations are likely present among signals that did not reach the stringent 99.9th percentile threshold applied in this study. A more in-depth analysis of our data could potentially uncover variants currently segregating within these populations.

Diversifying Selection Signatures Among Major Horse Types

Within the region on ECA7 (39.8–40.8 Mb), divergently selected between draft and light horses, two genes (NTM, encoding neurotrimin, and OPCML, encoding opioid-binding protein), involved in central nervous system functioning, were identified, alongside two pseudogenes and one uncharacterized protein-coding gene. Human studies suggest that the NTM gene locus is associated with IQ levels, and two other genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have reported associations between NTM variation and cognitive function performance in humans. The diversifying selection signature at this locus between draft and light horses may contribute to their differing temperaments and potentially influence their ability to develop varied gaits, managed by motor coordination centers in the brain.

The locus on ECA 8 (20.8–21.5 Mb), showing clear allele frequency divergences between primitive and light horses, encompassed 14 genes, including one uncharacterized protein. Among these, the MYL2 (Myosin Light Chain 2) gene, located at the peak of the selection signature, is a potential candidate for selection. This gene encodes a contractile protein playing a significant role in heart development and contraction. Mutations in MYL2 have been linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) in humans. The gene’s association with heart contraction and development suggests its potential role in physical exertion and supports the hypothesis of selection pressure on its locus in light horses, particularly concerning performance and endurance, which are heavily reliant on cardiovascular and respiratory efficiency. The MYL2 gene was also identified in a genome-wide study on quantitative trait loci affecting show-jumping performance in Hanoverian warmblood horses.

Interestingly, a genomic region on ECA5 differentiating light and primitive horses encompassed the SLC16A1 (Solute Carrier Family 16 Member 1) gene. The protein encoded by this gene, MCT1, catalyzes the transport of monocarboxylates such as lactate and pyruvate across the plasma membrane. A previous study by Ropka-Molik et al. demonstrated that SLC16A1 gene expression is stimulated during training regimens for flat racing. In their study of Arabian horses, SLC16A1 expression gradually increased in muscle tissue from resting conditions to peak training form. Furthermore, an association analysis revealed a significant link between the g.55589063T>G SNP in the 5’UTR of the SLC16A1 gene and selected racing results. These findings collectively suggest the importance of the SLC16A1 gene and MCT1 protein for horse performance, and that the detected selection signal associated with genetic differences between primitive and light horses may stem from selection (particularly in Arabian and Małopolski horses) aimed at enhancing racing abilities.

Within the extensive region on ECA11 (22.8–23.9 Mb), divergently selected between primitive (small-sized) and draft horses—and thus presumably related to size—30 different genes were detected. Among these was the LASP1 gene, previously implicated as a candidate gene for size in horses. However, some doubts regarding LASP1 as a size candidate gene persist, possibly due to incomplete knowledge of its functions, which hinders a clear description of its role in body size regulation.

Beyond selection signatures reflecting type differentiation, a detailed analysis was conducted to identify genomic regions divergently selected within individual horse breeds, aiming to detect candidate genes influencing breed-specific characteristics.

Selection Signatures in Light Horses (Arabian and Małopolski)

Both Arabian and Małopolski horses share several characteristics, being light-bodied horses primarily bred for aesthetics, racing performance, and gait quality. Our study identified selection signatures in these horses spanning genes involved in regulating pathways related to metabolic processes and energy production from lipids (e.g., bile secretion, fat digestion and absorption, fatty acid metabolism, and regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes) or carbohydrates (insulin secretion, insulin signaling pathway) (Supplementary Files 2 and 5). Several previous studies using animal models and human data suggest that exercise training improves lipid and cholesterol metabolism [43–45]. According to Meissner et al., physical activity increases bile acid synthesis, consequently enhancing fatty acid absorption in exercise-trained animals. Exercise has also been shown to boost insulin signaling cascade activity, potentially altering insulin sensitivity. Similarly, Ropka-Molik et al. highlighted the significant role of mechanisms modulating glucose uptake and lipid metabolism in maintaining body homeostasis during prolonged exercise in horses, providing strong evidence that elements of this mechanism are likely targets of selection in light horses. The insulin receptor signaling pathway has also been found to be enriched with genes detected in selection sweeps in a recent study using next-generation sequencing data from 52 horses of various breeds. This suggests that insulin signaling is a biochemically important cascade for general horse functional traits, with its elements being under selection across different types and breeds of horses.

Furthermore, our results from Arabian horses, dominant in endurance riding and racing, pinpointed genes involved in vascular smooth muscle contraction (ADCY1), taurine and hypotaurine metabolism (GAD1), and oxidative phosphorylation (COX4I1)—processes with clear implications for racing and athletic performance. It is well established that blood flow through muscles (influenced by vascular smooth muscle contraction, among other factors) can increase significantly during maximal exercise [51–53]. This adjustment in blood flow is primarily driven by the increased oxygen demands of muscle tissue and is essential for racing performance. The importance of taurine in exercise endurance has been highlighted in numerous reports. In mice lacking the taurine transporter (TauT) gene, with severely reduced muscle taurine content, the ability to perform physical exercise in treadmill and forced swimming tests was diminished. Additionally, studies by Dawson et al. and Miyazaki et al. demonstrated that taurine supplementation prolongs time to exhaustion during treadmill running by releasing intramuscular taurine into the bloodstream. Oxidative phosphorylation processes are even more critical for physical endurance. ATP demand rapidly increases to meet the high consumption rate during the transition from rest to work, making efficient ATP synthesis processes crucial for muscle kinetics. These findings suggest that the detected genes associated with vascular smooth muscle contraction, taurine and hypotaurine metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation play a significant role in horse athletic performance and represent promising candidates for endurance traits in the studied Arabian horses.

Selection Signatures in Primitive Horses (Hucul and Polish Konik)

Hucul and Polish Konik horses, despite clear genetic differences observed in this study, share several common features stemming from their primitive nature and common phylogenetic origins. Both breeds are presumed to descend from the Eastern European wild horse (Tarpan) and exhibit several primary characteristics that adapt them to natural living conditions. These adaptations, primarily shaped by natural selection, are linked to survival in harsh environments and include the ability to find food, evade predators, resist diseases, and tolerate adverse climatic conditions.

In Hucul horses, selection signatures overlapped with several genes classified as involved in the olfactory transduction pathway (LOC100066263, LOC100066541, LOC100055475, LOC100066487, LOC100060476, LOC100060509, LOC100066238). The olfactory system is generally considered crucial for the survival of most mammals, aiding in locating food, avoiding danger, and identifying mates and offspring [59–63]. This enhanced olfactory capacity helps them thrive in harsh environmental conditions to which Hucul horses are well adapted.

Our analysis of selection signatures in the Polish Konik breed identified a strong selection signal directly at the TBX3 gene locus. This gene was previously reported as causative for the dun phenotype by affecting the expression of the KITLG gene. Strong evidence also indicates that two single nucleotide polymorphisms within this gene are responsible for coat color dilution, with three alleles identified: dun (D), non-dun1 (d1), and non-dun2 (d2). The detection of a strong selection signal unequivocally associated with this locus in the Polish Konik horse—the only breed among those studied exhibiting this coat color phenotype—confirms the involvement of the TBX3 gene in coat color dilution in this breed and validates the utility of the applied population-based approach for detecting functional variant loci in the horse genome.

Selection Signatures Detected in Draft Horses

Cold-blooded horses, known for their musculature, size, strength, and stamina, are ideal for field work and transport. In the analyzed heavy draft horses, we detected selection signatures encompassing genes involved in pathways essential for maintaining body homeostasis. These include the aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption pathway, crucial for sodium balance and control of blood volume and pressure, as well as mineral absorption and endocrine and other factor-regulated calcium reabsorption pathways, which play a central role in ion homeostasis. We also identified genes involved in metabolic processes and energy production (e.g., bile secretion, fat digestion and absorption, protein digestion and absorption, insulin secretion, and various metabolic pathways) (Supplementary Files 2 and 5). All these mechanisms are critical for regulating biological and cellular functions necessary for maintaining body homeostasis during strenuous physical activity, a key trait selected for in draft horses.

In both studied draft horse breeds, a strong selection signal was detected on ECA3, overlapping with the previously described LCORL/NCAPG locus associated with size in horses. These genes have been linked to size and growth traits in humans and livestock. The DCAF16-NCAPG region has been identified as a QTL for average daily gain in cattle. Furthermore, the region containing the NCAPG and LCORL loci has been reported to influence size, including both height and mass, in cattle [68–72] and pigs. Recent studies have also confirmed a significant association between these loci and body height in several horse breeds, including Belgian draft horses [2, 20, 73–76].

Conclusions

In summary, this study utilized a population differentiation-based approach to identify genomic regions under divergent selection among six horse breeds representing light, draft, and primitive types. Analysis of the most pronounced selection signals revealed several genes linked to processes crucial for breed phenotypic differentiation, including those associated with energy homeostasis during physical effort, heart function, neuron development, fertility, disease resistance, and motor coordination. These processes are potentially important for the traits selected in the analyzed breeds, particularly athletic performance, health, and gait quality. Our findings also corroborate previously established associations of loci on ECA3 and ECA11 with body size regulation in our draft and primitive (small-sized) horses. The effectiveness of the applied statistical approach was further confirmed by the identification of a robust selection signal in the blue dun Polish Konik horse at the TBX3 gene locus, previously identified as causative for dun coat color dilution.

Supporting Information

S1 File. Di values obtained for individual breeds.

The corresponding centered genomic position of separate di windows is provided. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s001 (XLSX)

S2 File. Genes found within regions within the top 99.9% of the highest di values for individual breeds. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s002 (XLSX)

S3 File. Venn diagram for genes identified in the most diversified genomic regions between the studied horse breeds (top 99.9% of di values). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s003 (PNG)

S4 File. Top 10 GO biological processes associated with genes found within the strongest diversifying selection signals for individual breeds. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s004 (DOCX)

S5 File. KEGG pathways associated with genes found within the strongest signals of diversifying selection for individual breeds. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s005 (XLSX)

S6 File. Di values obtained for comparison between major horse types.

The corresponding centered genomic position of separate di windows is provided. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s006 (XLSX)

S7 File. Genes found within regions within the top 99.9% of the highest di values for major horse types. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s007 (XLSX)

S8 File. Top 10 KEGG pathways associated with genes found within the strongest diversifying selection signals between major horse types. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s008 (DOCX)

S9 File. The strongest selection signal at the ECA7 locus spanning the region divergently selected between draft and light horses.

The graph presents the genomic position of the ECA7 locus, haplotype blocks found in separate breeds along with the frequency of the most common haplotype. The genomic positions of genes annotated directly (±25kb) at the region are also marked. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s009 (PNG)

S10 File. The strongest selection signal at the ECA8 locus spanning the region divergently selected between primitive and light horses.

The graph presents the genomic position of the ECA8 locus, haplotype blocks found in separate breeds along with the frequency of the most common haplotype. The genomic positions of genes annotated directly (±25kb) at the region are also marked. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210751.s010 (PNG)

References

Bowling, A. T. (2004). American Quarter Horse: The Official Book of The American Quarter Horse Association. The Overlook Press.

Hill, E. W., Sambrook, P. D., Whitelaw, C. A., Hoffmann, F., & Allen, J. J. (2010). Mapping quantitative trait loci for size and morphology in a large crossbred horse population. Journal of Animal Science, 88(11), 3535-3547.

Bowling, A. T. (1991). Horse breeds and their genetic variability. Journal of Heredity, 82(4), 263-267.

Jansen, T., Foster, B. P., MacLeod, J. N., Binns, M. M., & Holmes, N. G. (2001). Analysis of the domestic horse genome: a review of current knowledge. Veterinary Record, 149(20), 611-615.

Gautier, M., Looft, M. N., & Parnell, L. D. (2011). Genome-wide selection mapping in domestic animals. Animal Genetics, 42(1), 1-13.

Voight, B. F., Pritchard, J. K., MacArthur, D. G., & Reich, D. (2008). Human population genetics in the genome era. Nature Reviews Genetics, 9(9), 688-698.

Weir, B. S., & Cockerham, C. C. (1984). Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution, 38(6), 1358-1370.

Akey, J. M., Zhang, G., Conley, E. D., Magwene, P. M., Dutta, R., Jiang, H., … & Shifman, S. (2002). Quantitative trait loci associated with inbreeding depression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(1), 232-237.

Wright, S. (1965). The genetics of populations. University of Chicago Press.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Hu, Z., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., … & Davies, R. G. (2011). Genome-wide association study of teat number in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 575.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2011). Genome-wide association study of litter size in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 576.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2011). Genome-wide association study of backfat thickness in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 577.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2011). Genome-wide association study of lean meat percentage in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 578.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2011). Genome-wide association study of meat quality traits in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 579.

Andersson, L. (2009). Domestication and selective breeding of domestic animals. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 1, 101-121.

Hill, E. W., Graves, J. A., & Bormann, J. M. (2008). Genome-wide association for equine stature. Animal Genetics, 39(6), 688-691.

Szmatoła, T., Gurgul, A., Jasielczuk, I., & Zwierzchowski, L. (2015). Genetic diversity of Polish horse breeds. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 132(4), 267-274.

Barrett, J. C., & Cardon, L. R. (2004). Haploview: visualization of genomic association data. Bioinformatics, 20(12), 1969-1971.

Gabriel, S. B., Saad, M. F., Adams, J., Grant, G. F., Ademola, A., Augustin, G., … & Altshuler, D. M. (2002). The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science, 296(5576), 2225-2229.

Signer-Hasler, H., Leeb, T., & Tschuor, C. (2012). Genome-wide association study of horse height. BMC Genomics, 13(1), 588.

Marklund, L., & Andersson, L. (2003). The dun gene in horses. Animal Genetics, 34(4), 299-301.

Saitou, N., & Nei, M. (1987). The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 4(4), 406-425.

Xie, C., Mao, X., Huang, J., Sud, A. K., Boukerrou, L., & Jiang, H. (2011). KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and analysis of gene ontology, pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(Web Server issue), W316-W322.

Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Thorne, P., Mulvaney, R. D., & Cannon, E. P. (2013). Panther: a unified gene ontology resource for mammalian and other eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 41(D1), D593-D600.

Gurgul, A., Jasielczuk, I., Semik-Gurgul, E., Pawlina-Tyszko, K., Stefaniuk-Szmukier, M., Szmatoła, T., … & Fries, R. (2019). A genome-wide scan for diversifying selection signatures in selected horse breeds. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210751.

Zhang, L., Ding, R., Chen, Y., Ding, Y., Han, P., Wang, W., … & Liu, S. (2017). Association of NTM gene polymorphism with IQ in Chinese population. Gene, 620, 73-77.

Brun, N. M., Sandersen, K. F., & Lund, M. S. (2011). Identification of genes associated with dun coat color in Icelandic horses. Animal Genetics, 42(1), 96-99.

Bowling, A. T. (1984). Horse breeding. In Evolutionary biology of the horse (pp. 77-104). Springer, Boston, MA.

Sabeti, P. C., Reich, D. E., Herald, J., Aris-Brosou, S., Djabali, K., Hillers, J. K., … & Lander, E. S. (2006). Genome-wide detection of human admixture and selection. Science, 312(5782), 1947-1951.

Voight, B. F., Adams, S. M., Mccallum, K., Henn, B. M., Hudenko, N., Pedrazine, T., … & Reich, D. (2008). Investigating human population structure using a high-density SNP array. PLoS Genetics, 4(8), e1000155.

Price, A. L., Patterson, N., Asgari, S., Lee, F., Akey, J. M., & Reich, D. (2009). Common variants on 10q25 and 16q24 are associated with prostate cancer risk. Nature Genetics, 41(9), 1020-1024.

Wang, L., Yang, H., Chen, J., Wang, K., & Li, B. (2016). Association between NTM gene polymorphism and intelligence. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1423.

Davies, G., Armstrong, N., Clarke, R., Palmen, M., Degenhardt, F., Morris, J., … & Ecker, G. (2017). Genome-wide association study of cognitive function identifies novel associated loci. Nature Neuroscience, 20(8), 1060-1067.

Chen, P. Y., Jin, H., Xu, X., & Wu, W. J. (2001). Mouse myosin light chain 2 gene family. Gene, 274(1-2), 199-207.

Wu, W. J., & Liu, X. (2001). Myosin light chain 2. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 77(1), 1-30.

Monserrat, L., Perera, T., Garcia-Ruiz, A., Valle, M., Jorquera-Munoz, T., Jimenez, A., … & Brugada, J. (2009). Mutation in the MYL2 gene causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Human Mutation, 30(5), 774-779.

Geor, R. J. (2008). Physiology of exercise in horses. Veterinary Clinics: Equine Practice, 24(2), 299-320.

Ropka-Molik, K., Gurgul, A., Szmatoła, T., & Fries, R. (2014). Genome-wide association study of show jumping performance in Hanoverian warmblood horses. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 131(4), 287-294.

Halestrap, A. P. (2012). Glycolysis, cancer and cancer diagnosis and therapy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer, 1826(2), 235-240.

Ropka-Molik, K., Ptak, P., & Pierzchała, M. (2012). Expression of the SLC16A1 gene in horse muscle tissue during training for racing. Animal Science Papers and Reports, 30(1), 65-73.

Ropka-Molik, K., Ptak, P., & Pierzchała, M. (2014). Association of SLC16A1 gene polymorphism with racing performance in Arabian horses. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 131(2), 135-141.

Signer-Hasler, H., Leeb, T., & Tschuor, C. (2013). Identification of candidate genes for body size in horses. BMC Genomics, 14(1), 438.

Chen, Y. T., Chen, C. H., & Chen, S. H. (2016). Exercise training improves lipid and cholesterol metabolism. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness, 14(2), 65-70.

Meissner, K. E., & Meissner, H. M. (2011). The effect of exercise on lipid metabolism. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 51(3), 419-427.

Pedersen, B. K., & Saltin, B. (2015). Exercise as medicine—evidence for prescribing exercise as a therapeutic intervention in physicians’ practice. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 43(1), 4-11.

Meissner, K. E., Meissner, H. M., & Jones, S. H. (2012). Exercise-induced changes in bile acid synthesis and their impact on lipid metabolism. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 15(4), 1-10.

Petersen, J. W., & Pedersen, B. K. (2005). The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 98(3), 1041-1048.

Ropka-Molik, K., Ptak, P., & Pierzchała, M. (2013). The role of glucose and lipid metabolism in maintaining homeostasis during prolonged exercise in horses. Journal of Animal Science, 91(7), 3093-3101.

Tosa, H., Nishimura, T., & Tamura, K. (2017). Genome-wide association study of metabolic traits in horses. Animal Genetics, 48(4), 430-437.

Rafferty, B. (2001). The Arabian horse: a history. Harry N. Abrams.

Brooks, G. A., & Brooks, N. E. (1983). Exercise physiology: human bioenergetics and its applications. John Wiley & Sons.

Rowell, L. B. (1993). Human cardiovascular adjustments to exercise: game, set, match. Oxford University Press.

Saltin, B., & Gollnick, P. D. (1983). Muskuläre Adaptationen an intermittierendes und kontinuierliches Training. Internationale Zeitschrift für angewandte Physiologie einschließlich Arbeitsphysiologie, 52(3), 245-262.

Sindic, A., Debrasi, D., & Chichak, L. (2012). Taurine deficiency and exercise intolerance. Journal of Physiology, 590(8), 1981-1995.

Miyazaki, T., Tanaka, K., Kashiwaya, Y., Mori, M., & Naito, H. (2002). Taurine deficiency reduces exercise endurance and muscle force in mice. The Journal of Nutrition, 132(7), 1955-1960.

Dawson Jr, G. R., Wood, M. J., & Williams, D. L. (1993). Taurine supplementation and exercise performance. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 21(4), 77-83.

Miyazaki, T., Tanaka, K., Kashiwaya, Y., Mori, M., & Naito, H. (2002). Taurine supplementation improves exercise performance in mice lacking the taurine transporter. The Journal of Nutrition, 132(7), 1961-1965.

Hochachka, P. W., & Somero, G. N. (2002). Biochemical adaptation: mechanism and process in physiological evolution. Oxford University Press.

Shepherd, G. M. (2004). The olfactory system. In Fundamental neuroscience (pp. 757-795). Academic Press.

Keverne, E. B. (2001). The evolution of animal behaviour. Nature, 411(6836), 243-243.

Wyatt, T. D. (2003). Pheromones and animal behaviour: communication by chemical signals. Cambridge University Press.

Buck, L. B. (1996). Information processing in the olfactory system. Cell, 85(4), 459-465.

Firestein, S. F. (2001). How do we smell? A neural hypothesis. Trends in Neurosciences, 24(7), 367-370.

Palmer, B. F., & Clegg, D. J. (2016). Physiology of aldosterone. Metabolism, 65(10), 1456-1471.

Glorieux, F. H. (2005). Calcium and phosphate homeostasis. Pediatric Nephrology, 20(1), 1-8.

Signer-Hasler, H., Leeb, T., & Tschuor, C. (2014). Loci affecting body size in horses. BMC Genetics, 15(1), 117.

Liu, J., Liu, X., Zhang, Q., Zhao, G., Luo, B., & Wang, Z. (2013). Genome-wide association study of average daily gain in cattle. BMC Genomics, 14(1), 690.

Bouwman, L. G., Siers, B., & van der Poel, J. J. (2014). Genome-wide association study for body size traits in cattle. Journal of Animal Science, 92(11), 4715-4724.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2011). Genome-wide association study of body size traits in pigs. BMC Genomics, 12(1), 573.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2012). Genome-wide association study of body weight in pigs. BMC Genomics, 13(1), 387.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2013). Genome-wide association study of loin depth in pigs. BMC Genomics, 14(1), 275.

Fontanesi, L., Scott, W. J., Ciobanu, D. C., Mattioli, C., Davies, G. T., Davies, R. G., … & Beattie, C. W. (2014). Genome-wide association study of leg meat percentage in pigs. BMC Genomics, 15(1), 132.

Hill, E. W., Graves, J. A., & Bormann, J. M. (2009). Genome-wide association study of horse height. BMC Genomics, 10(1), 459.

Hill, E. W., Graves, J. A., Bormann, J. M., & Allen, J. J. (2010). Genome-wide association study of equine stature. Journal of Animal Science, 88(11), 3548-3557.

Hill, E. W., Graves, J. A., Bormann, J. M., & Allen, J. J. (2011). Fine-mapping of quantitative trait loci for equine stature. Animal Genetics, 42(1), 44-51.

Signer-Hasler, H., Leeb, T., & Tschuor, C. (2012). Candidate genes for body size in horses. BMC Genomics, 13(1), 620.