Heart failure in dogs is a serious yet manageable condition that affects many pets, especially as they age. Whether caused by congenital issues or acquired diseases, it leads to symptoms like fluid buildup, weakness, and breathing difficulties. Understanding heart failure in dogs empowers owners to recognize early signs and seek timely veterinary care. This guide covers the most common underlying diseases, diagnostic tips, and practical management strategies to improve your dog’s quality of life.

For specialized care, consider consulting professionals at a village vet hospital familiar with cardiac issues in pets.

What Is Heart Failure in Dogs?

Heart failure in dogs occurs when the heart cannot pump blood effectively, often stemming from congenital or acquired heart diseases. It can impact the left side, right side, or both, resulting in congestion (backward failure) from fluid retention or low cardiac output (forward failure) causing weakness and fatigue.

The most frequent culprits in adult dogs are degenerative mitral valve disease (DMVD) and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Initial treatment typically involves a diuretic like furosemide, an ACE inhibitor such as enalapril, and pimobendan to enhance heart contractility. Additional drugs may be added based on progression.

Early detection through regular checkups is crucial, particularly for breeds prone to these conditions.

Progression to Congestive Heart Failure

As heart function declines, neurohormonal systems like the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone activate, increasing fluid volume, preload, and chamber stretch. This elevates hydrostatic pressure in pulmonary veins (left-sided) or vena cavae (right-sided), leading to pulmonary edema or ascites with pleural effusion.

Monitoring resting respiratory rates at home—ideally under 35 breaths per minute—helps owners spot progression early.

Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease (DMVD)

DMVD is the leading acquired heart disease in dogs, particularly small breeds like Cavalier King Charles spaniels and miniature poodles. It causes mitral (and sometimes tricuspid) valve regurgitation, resulting in left atrial and ventricular enlargement, systolic dysfunction, supraventricular arrhythmias, and pulmonary hypertension.

Not all DMVD cases progress to heart failure; only about 30% of asymptomatic dogs with heart enlargement develop clinical signs like pulmonary edema. Radiographic evidence of enlargement increases risk.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM)

DCM primarily affects the heart muscle, common in large breeds like Doberman pinschers and Great Danes. It features a prolonged asymptomatic phase (1-2 years), followed by arrhythmias, sudden death, or heart failure. Key changes include reduced left ventricular systolic function, chamber dilatation, and secondary mitral regurgitation.

Arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, ventricular premature complexes, and tachycardia are prevalent and often need separate treatment.

For traveling owners, reliable options like rover dog care can provide monitored care tailored to dogs with heart conditions.

Cough in Heart Failure: Heart or Respiratory Issue?

Coughing doesn’t always signal heart failure in dogs. It may stem from an enlarged left atrium compressing the mainstem bronchus or primary respiratory diseases like tracheal collapse.

A chronic, harsh cough ending in a gag, with good appetite and activity, suggests bronchial compression rather than active congestive heart failure (CHF). This can precede CHF and persist post-diuretic treatment.

Key questions for owners: Duration of cough? Harsh with gagging? Impact on appetite/activity?

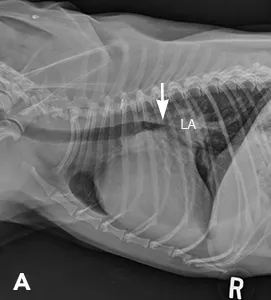

Right lateral thoracic radiographs showing mainstem bronchial compression in a shih tzu with DMVD

Right lateral thoracic radiographs showing mainstem bronchial compression in a shih tzu with DMVD

FIGURE 1A: Radiographs from a 14-year-old shih tzu on heart meds with chronic cough due to left atrial enlargement (arrow indicates compression). Good appetite, normal activity, resting rate 24 breaths/min.

Pulmonary edema in Cavalier King Charles spaniel with acute CHF

Pulmonary edema in Cavalier King Charles spaniel with acute CHF

FIGURE 1B: 9-year-old Cavalier with acute cough and dyspnea; note pulmonary venous enlargement and interstitial pattern (arrow).

A Real-Life Case Study

An 8-year-old neutered male bichon frise presents with 6 months of exercise-induced cough and a grade 3/6 left systolic murmur, now worsened to night coughing and labored breathing (grade 4/6 at apex).

Does this indicate heart failure? Signalment and signs suggest possible CHF from DMVD, but history, exam, and diagnostics confirm it.

| Scenario | Heart Rate (bpm) | Respiratory Rate (breaths/min) | Likely CHF? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 30 | Less likely |

| 2 | 160 | 60 | Consistent |

Scenario 2 aligns with sympathetic drive in CHF.

6 Practical Tips for Diagnosing and Managing Heart Failure in Dogs

1. Factor in Age and Breed (Signalment)

Young dogs (<2 years) lean toward congenital defects; older/small breeds toward DMVD; large breeds toward DCM. Cavaliers show murmurs by age 4; Dobermans face 60% DCM lifetime risk peaking at 7 years.

FIGURE 2: Lead II ECG showing sinus tachycardia (175 bpm) in CHF dog.

FIGURE 3: Lead II ECG (80 bpm irregular) in dog with murmur and cough but no CHF.

2. Gather Detailed History and Exam Findings

History supporting heart failure:

| Finding | Implication |

|---|---|

| Progressive tachypnea | Pulmonary edema likely |

| Syncope/collapse | Arrhythmias or low output |

| Ascites/pleural effusion | Right-sided failure |

Exam: Left apical murmur (DMVD hallmark), tachycardia (vs. arrhythmia), gallop rhythms, weak pulses.

3. Time Diagnostics Appropriately

Thoracic radiographs assess enlargement, edema; start diuretics if dyspneic. Biochemistries monitor kidneys/electrolytes. Echocardiography defines disease type post-stabilization, spotting complications like shunts.

4. Account for Comorbidities and Drug Effects

DMVD/DCM therapy: furosemide + pimobendan + ACE inhibitor. Watch kidneys (NSAIDs worsen GFR), electrolytes, pulmonary hypertension in protein-losing diseases.

When boarding is needed, opt for experienced providers like senior dog boarding for older dogs with heart issues.

5. Empower Owners for Home Management

Rechecks every 2-4 months; teach signs (worsening cough, lethargy); track resting breaths (<35/min). Promote palatable low-salt diets, light exercise. Measure success by quality of life.

Reliable sitters via trusted pet sitters can assist with medication routines.

Explore stay dog boarding for stress-free stays during vet visits.

6. Partner with a Cardiologist

Refer for complex cases; follow ACVIM guidelines (2009) on staging/treatment.

Conclusion

Heart failure in dogs, driven by DMVD or DCM, requires vigilant monitoring and tailored therapy for optimal outcomes. By recognizing signs like cough or tachypnea, using diagnostics wisely, and involving owners, many dogs enjoy extended, comfortable lives. Consult your vet promptly and prioritize quality of life—your furry friend depends on it.

References

- Atkins C, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:1142-1150.

- Borgarelli M, et al. Survival characteristics… J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:69-75.

- Borgarelli M, Haggstrom J. Canine degenerative myxomatous mitral valve disease… Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010;40:651-663.

- Wess G, et al. Prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy in Doberman Pinschers… J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:533-538.

Editor’s Note: For the latest on congestive heart failure, see peer-reviewed updates from veterinary sources.