Gouldian finches, like all living beings, possess unique personalities that significantly influence their behavior. Recognizing these individual traits is key to understanding why a particular finch acts the way it does. While they may look similar, no two Gouldian finches are exactly alike in personality. These distinct personalities lead to individual likes and dislikes, and it’s a misconception that all Gouldian finches share the same preferences.

The vocalizations of Gouldian finches are also individualistic. Male finches have their own unique songs, which can vary slightly from one male to another. While females do not sing in the same way, they produce a range of sounds, some common to all finches, and others uniquely their own. This individual pitch and vocal pattern is crucial for offspring recognition, allowing young finches to identify their parents. Male songs are often complex and quiet, varying with the season, and they can even learn parts of songs from other birds, including different species. One notable instance involved a male Gouldian finch that perfectly mimicked a Cuban finch’s song in pitch, volume, and length. Unfortunately, this bird was accidentally sold with other finches and never seen again, highlighting the importance of careful separation of young birds from breeding stock.

A fascinating social experiment demonstrated that Gouldian finches can indeed identify individual humans. Finches kept in a large aviary within the owner’s living space were observed reacting differently to various people. When the owner approached the aviary, the finches would gather near the wires as if to greet him. However, when friends, even those who looked similar and wore similar clothes, approached, the birds showed no interest. Even the owner’s brother, who bore a strong resemblance, elicited only a brief approach before the birds retreated when he spoke. The owner’s presence, however, consistently drew the usual enthusiastic response. This repeated observation confirmed that the finches recognized the owner by both face and voice. Any stranger entering the room would cause noticeable panic or excitement within the aviary.

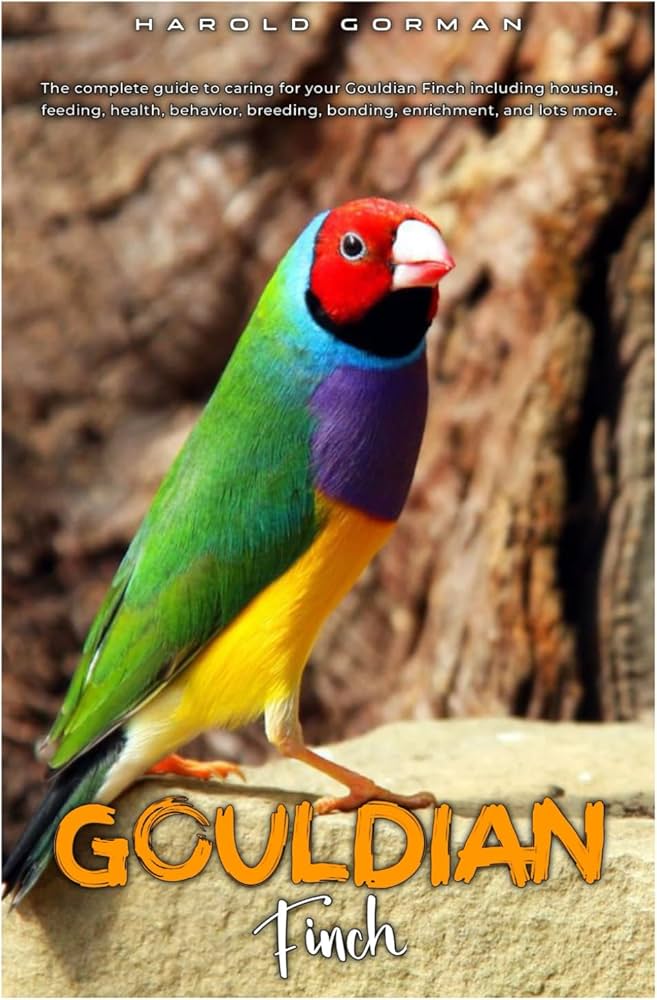

The head color of a Gouldian finch plays a significant role in its temperament. Observations over many years indicate that black-headed Gouldians are the least aggressive. Red-headed finches tend to be more feisty and prefer perching higher in the cage. Yellow-headed Gouldian finches, on the other hand, often assert themselves and like to be at the top of the pecking order. The author has experienced more challenges with yellow-headed finches, particularly during the breeding season, often requiring them to be housed separately in a larger flight to ease tension. Separating finches by head color during breeding is recommended, as natural selection favors hens choosing mates with the same head color. Breeding different head colors together can lead to reduced egg-laying, a higher proportion of male offspring, and decreased chick survival rates. While some experiments suggest red-headed finches are the most dominant, personal experience indicates that yellow-headed finches present more difficulties.

After the breeding season concludes, the aviary becomes calmer. Male singing diminishes, and aggression levels decrease. It is advisable to keep juveniles with their parents until their annual molt to allow them to learn essential social skills and feeding habits. Without this period of learning from adult role models, young finches may become inadequate parents themselves. Selling or giving away juveniles too soon, especially within weeks of leaving the nest, can result in mortality, poor parenting, or other behavioral issues, similar to human children raised without adult guidance. Juveniles should ideally remain with their parents until after their first annual molt, and potential buyers should avoid purchasing birds during or just before this stressful period, as they are at their weakest then.

To enhance the well-being of Gouldian finches, providing privacy or anti-stress perches is beneficial. These perches, often wide enough for a single bird and with sides to block visual contact, are useful in large aviaries, especially when chicks are reluctant to leave their parents or when other birds are pestering them. Although Gouldian finches are flock birds, they also require solitary time to relax. An overcrowded aviary can significantly increase stress levels, making birds susceptible to illness. While chasing within the aviary might appear aggressive, it can also signify playfulness, mate selection, or the establishment of a pecking order.

Remarkably, hens that were in conflict during the breeding season can often be observed peacefully sitting together after it ends. This is likely due to their depleted energy reserves and the absence of a nest to defend. Gouldian finches can exhibit intense aggression over nesting sites, but can become very placid once breeding is complete. Some keepers opt for smaller breeding cages to reduce stress and improve breeding success, while others prefer colony breeding despite potential tensions. The author employs both methods, choosing based on the individual birds’ characters.

Following a demanding breeding season, observe birds that appear unusually fluffed up or larger than normal, sitting quietly alone. These individuals require careful examination. If illness is suspected, isolate the bird in a hospital cage with supplemental heat and close monitoring. Prompt isolation of any sick bird is crucial to prevent the spread of disease. Juveniles are particularly vulnerable and may succumb to various illnesses, but swift treatment often leads to recovery. In the author’s experience, juveniles with parents of different head colors appear more at risk for “going light syndrome.” Adult birds that have raised large clutches or bred multiple times in a year also warrant close attention.

A month or two after the breeding season, adult plumage may lose its vibrancy and tidiness, with some birds exhibiting baldness, more commonly in hens than males. Baldness can stem from genetic factors, mites, poor nutrition, or stress. Feathers typically regrow after the next annual molt, resolving the baldness. Documenting molting periods is important to track recovery. If baldness persists after a molt, review the records to confirm the bird completed its molting cycle. Various molt types exist, affecting mood and behavior, potentially causing irritability, reduced sociability, decreased activity, and even flight impairment. During molting, finches often prefer solitude, and aggression levels are at their lowest.

Providing fresh bathing water daily is essential, along with regular cleaning of the bath. While bathing frequency decreases in cooler weather, it remains a daily activity. Bathing helps birds stay clean and cool, and it stimulates the preening gland. The oil produced during preening, when exposed to sunlight (UV rays), converts to vitamin D3, which the bird can ingest. This oil is distributed over the feathers, maximizing vitamin D3 absorption. Although supplemental vitamin D3 is available, natural sunlight is superior.

Observing Gouldian finch tails reveals their importance in communication. During courtship, tails are pointed towards each other, signaling interest. Males may point their tails towards another perched male as a friendly gesture, a behavior also seen in hens. This tail-pointing appears to indicate interest, greetings, or attention towards favored items like food, baths, or nesting boxes. When a tail points upwards, it often signifies an attempt to chase another bird away, stress, anger, or general health issues. Males have been observed pointing their tails downwards primarily while singing or reaching upwards. A tail held in a normal, straight position typically holds no specific meaning. These observations are personal findings, not officially documented.

Gouldian finches clinging to cage wires or appearing to seek escape often indicate an unsuitable environment: cage too small, too dark, extreme temperatures, insufficient perches, boredom, overcrowding, or an aggressive cage-mate. This behavior is particularly common when moving a finch from a large flight to a smaller cage. Close observation of the setup is necessary to identify and rectify the cause promptly to prevent stress, illness, and potential death.

Stargazing, characterized by a finch tilting its head back and forth, sometimes so far as to fall off its perch, is often mistaken for twirling. It is frequently linked to stress or a feeling of confinement and can usually be resolved through environmental adjustments without medication. The bird may repeatedly fall backward before regaining its perch.

Twirling, unlike stargazing, is more pronounced and involves head tilting at odd angles, even upside down, leading to rolling. Severe cases are almost always related to disease, genetics, parasites, viral infections, trauma, or injury. Birds exhibiting these symptoms require immediate isolation in a clean cage with low perches (no more than 2 inches) and shallow floor-level food and water dishes.

Constant scratching and beak wiping are strong indicators of parasite infestation. While scratching may resemble preening, close observation reveals differences. Persistent beak wiping suggests parasites like mites, necessitating prompt treatment for all birds in the affected area.

Excessive beak wiping and head shaking often point to parasites or protozoa. Birds may repeatedly wipe their beaks on surfaces, attempting to dislodge irritants. Head shaking can also occur, sometimes mimicking feeding behavior even without young present, indicating bacterial infections or crop parasites. These symptoms collectively suggest mite infestation, blockages, bacterial infections, or protozoan issues.

Wing flipping or twitching can be attributed to stress or vitamin deficiency. Ensuring proper vitamin supplementation can help rule out deficiency, focusing attention on stress factors. While some suggest a genetic basis, it’s considered unlikely. Often, a lack of a clear solution leads to attributing the problem to genetics.

Persistent pecking at feet and legs is frequently caused by Scaly Mite (Knemidokoptes), a microscopic parasite that damages skin around the beak, eyes, face, toes, and legs, and can even affect feather follicles. Untreated, it can lead to deformities, limb loss, or beak damage. These burrowing mites feed on blood and require thorough treatment, including replacing wooden perches and frequent cage sterilization. Moxidectin is often recommended for long-term eradication.

Butt pumping, where a bird rapidly thrusts its bottom up and down, usually signifies something stuck around the vent, constipation, a sore vent, internal parasites, an abdominal infection, or accumulated droppings.

Poor or weak flight can result from various factors including age, illness, molting, malnutrition, feather parasites, or injury. A thorough examination is needed to determine the exact cause. The author experienced a flock where several birds progressively lost the ability to fly, perch, and eventually died, with no identifiable cause despite extensive testing and veterinary examination.

Consistently standing on one foot can indicate scaly mites, foot injury, discomfort from incorrect perches, bumblefoot, fractures, skin cracks leading to infection, obesity, burns, foreign objects, leg strain, nail overgrowth, dislocation, muscle pulls, or toe problems. Regular checks of the birds’ feet are essential.

Constant pecking at one wing may signal injury, such as a drooping wing, poor flight, or growths. Examination of the wing for lumps, fractures, or bruising is recommended. Pecking at both wings can indicate injury to both or a mite/lice infestation. Droopy wings may suggest underlying illness or emotional distress, though they can also occur temporarily after bathing.

Eating in darkness after lights out suggests a problem, possibly “Going Light” syndrome, characterized by continuous eating without weight gain due to conditions like Avian Gastric Yeast, internal parasites, protozoa, or blockages. This is often seen in juveniles or adults with poor nutrition. Affected birds require immediate placement in a hospital cage with heat and expert assessment. The opposite scenario, a bird refusing food and water while losing weight, also warrants urgent attention.

Shivering, though not observed by the author in their birds due to proper keeping conditions, is sometimes reported. Chicks raised in cold environments may exhibit shivering later in life, struggling to maintain warmth. Breeding Gouldian finches in cold climates is detrimental, as their native habitat in Queensland, Australia, rarely experiences snow. Acclimatizing species to new climates is a gradual, millennia-long process. While Gouldian finches can tolerate short cold spells, prolonged exposure is harmful.