Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) is a significant skeletal disorder and a primary concern in veterinary medicine. While screening programs typically categorize CHD into five classes, the underlying phenotype involves numerous sub-traits that can ultimately lead to debilitating osteoarthritis (OA). The development of OA is a complex process affecting multiple joint tissues, including bone, cartilage, synovial membrane, and ligaments. Due to this complexity, genetic discoveries related to CHD have been challenging, necessitating large, well-characterized study cohorts for each breed.

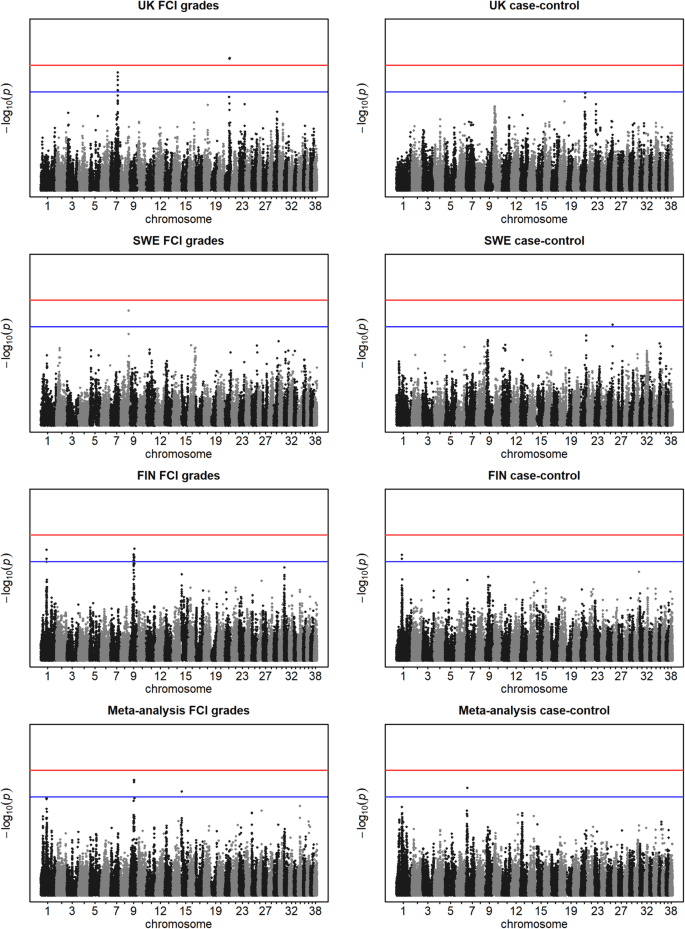

This study reports substantial progress in identifying genetic factors for key CHD traits in German Shepherds, mapping three new loci on different chromosomes. A locus on chromosome 1 is associated with OA and the FCI hip score, while loci on chromosomes 9 and 28 are linked to FHCDAE, a measure of hip joint incongruity. Furthermore, two suggestive loci on chromosomes 9 and 25 were identified for OA, Norberg Angle (NoA), and various FCI hip score comparisons. The locus on chromosome 1 demonstrates association with both OA and the FCI hip score, particularly when using a relaxed case definition. It’s important to note that this study partially utilizes data from a previous work by Mikkola et al. (2019), and therefore, should not be considered an independent replication.

Genetic Loci and Candidate Genes in German Shepherds

The locus identified on chromosome 1, situated between NOX3 and ARID1B, shows a stronger association with OA than with the FCI hip score. While the precise functions of these genes in CHD development are not fully understood, NOX3, a member of the NADPH oxidase family, is implicated in articular cartilage degradation. NADPH oxidases are involved in generating reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide, which can oxidize cartilage collagen cross-links, initiating degradation. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) BICF2P468585, with the strongest association, is located upstream of NOX3, and another SNP, BICF2S23248027 (rs21911799), is within an intron of NOX3. Although NOX3 is primarily expressed in the inner ear and fetal tissues, its potential role in synovial inflammation is still being investigated. Protein-protein interaction databases suggest a possible interplay between NOX3 and matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMPs), enzymes known to degrade the extracellular matrix and implicated in CHD and OA. Additionally, NOX3 may interact with TRIO, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and TIAM2, which modulates Rho-like protein activity, both of which are considered candidate genes for CHD. ARID1B is involved in chromatin remodeling and has been linked to joint laxity in Coffin-Siris syndrome patients.

Previous research has identified several loci associated with OA, but none overlap with the loci discovered in this study. Discrepancies with prior findings may be attributed to genetic heterogeneity across different study populations, variations in analytical methods, or differences in phenotyping approaches for evaluating OA.

On chromosome 9, a locus near the NOG gene is associated with the incongruity trait FHCDAE. The association with NoA was weaker, likely due to the higher inter-observer variability in assessing NoA compared to FHCDAE. Previous research identified protective regulatory variants upstream of NOG with an inverse correlation between their in vitro enhancer activity and healthy hips in German Shepherds. While the exact contribution of NOG to FHCDAE is unclear, it may provide insights into reduced joint congruity. Decreased noggin activity could potentially enhance acetabular bone formation through bone morphogenic protein (BMP) signaling, aiding in the repair of damage from mechanical wear in developing dogs. Delayed ossification of the femoral head has also been linked to later-life CHD. NOG is vital for numerous developmental processes, including joint and skeletal development. In humans, NOG mutations cause congenital disorders with abnormal joints, and in mice, the absence of Nog leads to severe limb joint defects. Conversely, overexpression of Nog in mice results in osteopenia and reduced bone formation.

The third genome-wide significant locus, also associated with FHCDAE, is on chromosome 28. This region contains CACUL1, a cell-cycle-associated gene, and NANOS1, which upregulates MMP14 (membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase, MT1-MMP). MT1-MMP is a potent collagenolytic enzyme and has been implicated in synovial invasion in human rheumatoid arthritis. The interplay between NANOS1 and MMP14 warrants further investigation in tissues relevant to CHD. Intriguingly, chromosome 28 has been previously associated with NoA in studies including German Shepherds. While this study did not find an association with NoA on chromosome 28, the previously reported locus is geographically close to the FHCDAE locus, suggesting potential overlap or distinct but related genetic influences.

Additional loci with suggestive associations for NoA and OA were found on chromosomes 9 and 25, and for FCI hip score on chromosome 9. These loci contain candidate genes such as LHX1, AATF (on chromosome 9), and SLC7A1 (on chromosome 25). LHX1 is a candidate for OA, showing differential methylation and upregulation in the disorder. SNPs near LHX1 also showed a suggestive association with CHD in a prior study. AATF is located near LHX1, and both genes have been linked to macrophage inflammatory protein 1b (MIP-1b) levels, a cytokine increased in OA synovial fluid. SLC7A1 is a transporter for cationic amino acids, and L-arginine metabolism can influence OA through the nitric oxide pathway.

Understanding the Complexity of CHD

The identification of multiple loci containing candidate genes involved in diverse biological pathways highlights the complexity of CHD pathophysiology. Some genes may exert their influence indirectly through interactions within complex genetic networks. Similar to findings by Sánchez-Molano et al. (2014), the polygenic nature of CHD necessitates large sample sizes for detecting significant genetic associations. It is plausible that even larger cohorts could uncover additional loci with smaller effects.

Beyond sample size, accurate and reliable phenotyping is crucial for studying complex traits like CHD. Standardized, high-quality radiographs and a limited number of assessors are essential to minimize inter-observer bias in FCI scoring. More precise measures of joint laxity, such as the distraction or laxity index, could aid genetic discovery by mitigating confounding factors that affect NoA and FHCDAE assessments, particularly when laxity is not apparent in standard extended-view radiographs. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the genetic underpinnings of CHD and to translate these findings into improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for affected dogs.