Heartworm disease, caused by the parasite Dirofilaria immitis, is a serious and potentially fatal condition primarily affecting dogs. As a responsible pet parent, you might naturally wonder about the potential for transmission to humans. The direct answer to “Can A Person Get Heartworms From A Dog” is no, not directly. Humans cannot contract heartworms directly from their infected dogs. However, understanding the intricate lifecycle of this parasite reveals a more nuanced answer regarding human exposure and potential, albeit rare, infection.

While heartworms are well-known for their devastating effects on canine health, humans are considered “accidental hosts.” This means our bodies are not a suitable environment for the heartworm larvae to fully mature and reproduce. Even so, human cases of Dirofilaria immitis infection, known as human pulmonary dirofilariasis, do occur, though rarely. These cases highlight the importance of understanding the parasite’s transmission and the symptoms it might cause in humans, which often mimic more serious conditions.

What Exactly Are Heartworms?

Heartworms (Dirofilaria immitis) are a type of roundworm parasite. In their definitive host, typically dogs, these worms live in the heart, lungs, and associated blood vessels. They can grow up to a foot in length and, if left untreated, can lead to severe heart failure, lung disease, and other organ damage. The presence of heartworms can significantly compromise a dog’s health, causing symptoms ranging from a mild cough and fatigue to difficulty breathing and a swollen belly. Understanding how worms pass between dogs is crucial for pet owners, though heartworms have a unique transmission pathway compared to other common intestinal worms.

How Do Humans Contract Heartworms?

The transmission of heartworms, whether to dogs or humans, always involves an intermediate host: the mosquito. This tiny insect plays a critical role in the heartworm lifecycle. When a mosquito bites an infected dog, it ingests microscopic heartworm larvae, called microfilariae, circulating in the dog’s bloodstream. These microfilariae then develop into infective larvae within the mosquito over a period of 10 to 14 days, depending on environmental conditions.

Once these infective larvae are present, if that same mosquito then bites another dog or, rarely, a human, it can transmit the larvae. So, the direct answer remains: a person cannot get heartworms by petting an infected dog, or even through direct contact with an infected dog’s blood. Transmission always requires an infected mosquito bite.

The Heartworm Lifecycle in Humans

In humans, the story of the heartworm larvae takes a different turn. When infective larvae are deposited under a human’s skin by a mosquito bite, they migrate through subcutaneous tissues and eventually make their way into the bloodstream. Unlike in dogs, where the worms mature and reproduce, the human body is an “unsuitable environment” for Dirofilaria immitis. The larvae typically cannot complete their full maturation process into adult worms, nor can they reproduce.

Instead, the larvae usually die off before reaching maturity. These dying or dead worms then often embolize, meaning they get lodged in small blood vessels, most commonly in the lungs. This can cause a localized inflammatory reaction, leading to the formation of small, often coin-shaped, nodules. These pulmonary nodules are the most common manifestation of human heartworm infection.

Symptoms of Heartworm Infection in Humans

The vast majority of human heartworm cases are asymptomatic, meaning individuals show no noticeable symptoms. The pulmonary nodules are frequently discovered incidentally during routine chest X-rays or CT scans performed for other medical reasons. When symptoms do occur, they are typically non-specific and can include:

- Cough

- Chest pain

- Mild fever

- Hemoptysis (coughing up blood, rare)

- Wheezing

It’s important to note that even in cases where an individual is infected with a parasite, peripheral eosinophilia (an elevated level of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell, in the blood) is only found in a small percentage of cases, approximately 6.5–15%. This often makes diagnosis more challenging as the expected parasitic marker may be absent.

The “Coin Lesion” Conundrum

One of the most concerning aspects of human pulmonary dirofilariasis is how the resulting pulmonary nodules are perceived. In a clinical setting, especially in individuals with a history of smoking or other risk factors, these nodules are often initially presumed to be malignant (cancerous). This necessitates further, sometimes invasive, diagnostic procedures such as biopsies to rule out cancer.

For example, a case study described a 48-year-old man, a smoker, who was found to have multiple asymptomatic pulmonary nodules during imaging for another condition. A biopsy of the largest nodule revealed a necrotic granuloma, consistent with a parasitic infection, after other fungal and bacterial causes were ruled out. This clinical picture was consistent with a D. immitis infection, underscoring the diagnostic dilemma posed by these parasitic lesions.

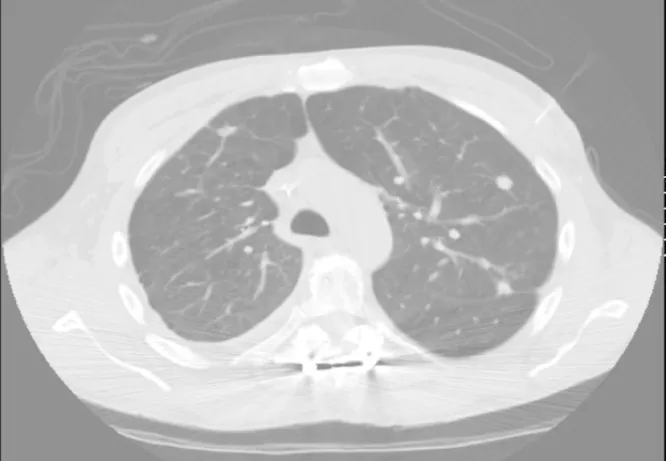

CT scan showing multiple pulmonary nodules, with the largest measuring 1.4 cm x 1.2 cm in the left lung.

CT scan showing multiple pulmonary nodules, with the largest measuring 1.4 cm x 1.2 cm in the left lung.

This image, though clinical, illustrates how these nodules appear on a CT scan, often prompting concerns about malignancy.

Diagnosing Human Dirofilariasis

Diagnosing human dirofilariasis can be difficult because of its asymptomatic nature and the non-specific symptoms it might present. The definitive diagnosis is often made after a biopsy of a pulmonary nodule reveals the presence of a necrotic granuloma, which is an inflammatory reaction to the dying worm. Sometimes, parts of the worm itself can be identified under the microscope.

Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Dirofilaria-specific antibodies, exist, but they are not commonly available and can sometimes show cross-reactivity with other filarial infections, leading to inaccuracies. Therefore, most cases are diagnosed based on microscopy findings during a biopsy.

Challenges in Diagnosis

The absence of typical parasitic markers like eosinophilia in many cases, combined with the difficulty in directly identifying the parasite in tissue samples, adds to the diagnostic challenge. It emphasizes the importance for healthcare providers to consider human pulmonary dirofilariasis as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with asymptomatic solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules, especially in regions where heartworm is endemic in dogs and mosquito populations are high. This consideration is particularly relevant when other common causes of lung nodules, such as fungal or mycobacterial infections, have been ruled out.

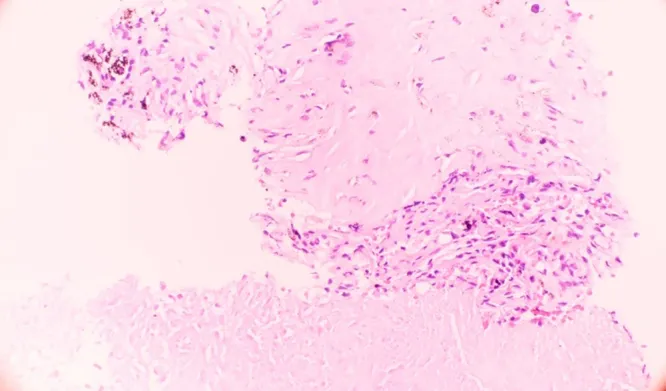

Microscopic view of a parasitic nodule in human lung tissue, demonstrating a necrotizing granuloma with histiocytes and fibrosis at the edge.

Microscopic view of a parasitic nodule in human lung tissue, demonstrating a necrotizing granuloma with histiocytes and fibrosis at the edge.

This microscopic image shows the typical granulomatous reaction in lung tissue that indicates a parasitic infection, often seen in human heartworm cases.

Understanding Your Risk: Can Your Dog Give You Heartworms Directly?

To reiterate, your dog cannot directly transmit heartworms to you. The presence of heartworms in your dog does not put you at direct risk through contact, petting, or even their saliva. The sole vector for transmission to both dogs and humans is an infected mosquito.

Therefore, owning a dog, even an infected one, is not considered a direct risk factor for human heartworm infection. Instead, the risk factors are related to the environment:

- Prevalence of infected dogs in the area: The more infected dogs (both stray and domesticated) in a region, the higher the reservoir for the parasite.

- Density of the mosquito population: More mosquitoes mean more opportunities for transmission.

- Degree of human exposure to mosquito bites: Spending time outdoors in areas with high mosquito activity increases the chance of being bitten by an infected mosquito.

If your dog is ill, ensuring they receive proper veterinary care, including diagnostics and flea, tick, and intestinal worm treatments for dogs, is paramount for their health and helps reduce the overall parasite burden in the environment. While heartworm is distinct, this comprehensive approach to parasite control contributes to a healthier ecosystem for both pets and people. You can also explore options like flea medicine in pill form for dogs for convenient prevention.

It’s also worth noting that other parasites can pose zoonotic risks, so understanding broader pet health is important. For example, some pet owners wonder can humans get ear mites from dogs or cats? While different from heartworms, knowing these possibilities helps maintain overall family health. Should your dog exhibit signs of other parasitic issues, consult your vet for the effective remedies for ear mites in dogs or other conditions.

Prevention: Protecting Both Your Pet and Your Family

While human heartworm infection is rare, prevention is always the best approach. Protecting your dog from heartworms is the most effective way to reduce the overall prevalence of the parasite in your community, thereby indirectly lowering the risk for humans.

Here’s how to safeguard your pet and, by extension, your family:

- Consistent Heartworm Prevention for Dogs: Administer veterinarian-prescribed heartworm preventatives to your dog year-round. These medications are highly effective at killing heartworm larvae before they can mature.

- Mosquito Control: Reduce mosquito populations around your home by eliminating standing water where mosquitoes breed. Use insect repellents when spending time outdoors, especially during dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active.

- Regular Veterinary Check-ups: Ensure your dog receives regular check-ups, including annual heartworm testing, to catch any potential infections early.

By taking these proactive steps, you contribute to a healthier environment for everyone, minimizing the risk of heartworm infection for your beloved canine companion and the extremely rare, accidental infection in humans.

Conclusion

While the question “can a person get heartworms from a dog” is technically answered with a no, the journey of the Dirofilaria immitis parasite highlights a rare but medically significant risk to humans through mosquito bites. Humans are accidental hosts, meaning the parasite typically doesn’t fully develop, often resulting in pulmonary nodules that can be mistaken for more serious conditions. The key takeaway for pet owners is that protecting your dog with consistent heartworm prevention is the best defense against this parasite for both your pet and the wider community, indirectly reducing any potential human exposure. Always consult your veterinarian for the best heartworm prevention strategy for your dog, and your doctor if you have concerns about your own health.

References

- Huston JM, Al-Saffar A, Khoujah D. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;22:188-190. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.07.009

- The American Heartworm Society. Current canine guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in dogs. Heartworm society website. 2014. http://www.heartwormsociety.org/

- Asim K, Mahvash Z, Hamid R, et al. Isolated pulmonary nodule due to Dirofilaria immitis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(11):953-954.

- Ro JY, Tsakalakis PJ, White VA, et al. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: the great imitator of primary or metastatic lung tumor. A clinicopathologic study of seven cases. 1989;92(1):44-53.

- Billingsley K, et al. A review of human pulmonary dirofilariasis and its imaging manifestations. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:468240.

- De Magelhaes PC. Description of Filaria bancrofti and Filaria immitis in Brazil. Jpn J Parasitol. 1958;7(6):613.

- Mazzola S, et al. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:254.

- Al-Balawi MM, et al. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: a case report and literature review. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(10):1501-1504.

- Gutierrez Y. Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. Oxford University Press; 2000.