The vibrant Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) is a familiar sight for many, often recognized by its striking blue plumage, white breast, and distinctive crest. While their brilliant colors are immediately captivating, a deeper look into their behavior reveals a surprisingly complex and intelligent species. This article delves into the fascinating social structures, communication methods, and resourcefulness of the Blue Jay, offering insights beyond their common backyard appearances.

Social Structure and Mating Habits

Blue Jays, like other members of the corvid family, exhibit intricate social systems. Primarily, they are monogamous, forming strong pair bonds that serve as the foundation of their social structure. Unlike some birds, Blue Jays are not strongly territorial, which allows multiple pairs to share the same feeding grounds harmoniously. However, an interesting shift occurs towards the end of the breeding season in late summer, when Blue Jays tend to form larger flocks.

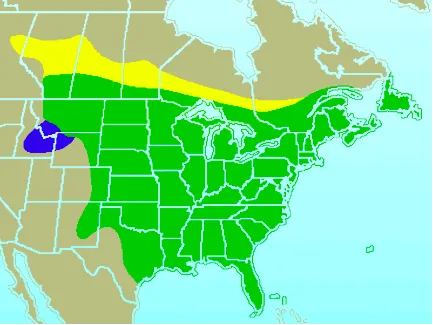

Migration patterns also play a role in their social dynamics. Many Blue Jays from the northern United States migrate south for the winter, while a smaller population remains in their nesting areas year-round. Studies in bird sanctuaries have indicated that these resident groups can be quite stable, with banded jays returning to the same feeding stations over successive winters, and even their offspring following suit. This suggests a bond that extends beyond mere resource availability, pointing to a form of social cohesion within these wintering groups. The exact factors dictating migratory behavior – whether primarily driven by younger birds seeking better food sources or by older and younger jays migrating at equal rates – remain a subject of ongoing ornithological debate.

Dominance and Aggression

Within the breeding pair, males typically display dominant behavior over females. Studies have observed a significant imbalance in interactions, with females rarely winning dominance contests against males. While males are generally larger than females, this size difference is often marginal, leading researchers to attribute male dominance largely to a more aggressive nature. Males tend to be more involved in social interactions. Interestingly, a temporary shift in aggression occurs just before the breeding season, with males becoming less aggressive and females becoming more so. This is thought to be linked to “nesting phenology” and increased energy demands for females preparing for egg-laying and nesting. Despite this temporary shift, male dominance generally persists. Distinguishing between male and female Blue Jays from a distance can be challenging, as their physical appearance is largely identical, a fact that even professional ornithologists acknowledge.

A diagram illustrating dominance interactions between male and female Blue Jays at a feeder.

A diagram illustrating dominance interactions between male and female Blue Jays at a feeder.

Remarkable Resourcefulness and Tool Use

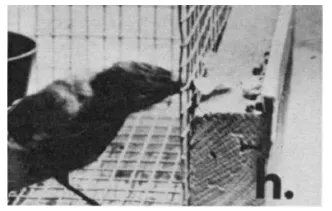

One of the most captivating aspects of Blue Jay behavior is their remarkable resourcefulness, particularly their capacity for tool use. Research has documented instances where Blue Jays, when faced with challenges in reaching food, have ingeniously used available materials as tools. In laboratory settings, a Blue Jay was observed using pieces of newspaper to retrieve food pellets that were otherwise out of beak’s reach. When presented with various items like paper clips, plastic ties, feathers, and straw grass, the bird successfully employed these objects to access the inaccessible food. Further experiments showed that a significant portion of other Blue Jays in the colony could also learn and apply this tool-using behavior. This adaptability highlights their cognitive abilities and problem-solving skills.

An illustration showing a Blue Jay using a piece of paper as a tool to reach food outside its cage.

An illustration showing a Blue Jay using a piece of paper as a tool to reach food outside its cage.

Sophisticated Communication and Mimicry

Blue Jays possess a diverse repertoire of vocalizations and are known for their ability to imitate the calls of other birds. These mimicked calls are often employed strategically, notably in instances of kleptoparasitism – the act of stealing food from other animals. Blue Jays have been observed imitating the calls of birds of prey, such as the red-shouldered hawk. By mimicking a hawk’s alarm call, they can cause other birds to flee from their food sources, allowing the Blue Jay to swoop in and claim the unattended meal. Whether this complex behavior evolved primarily as a defensive measure to warn of nearby predators or as a deceptive tactic for acquiring food remains a subject of interest, showcasing their clever and manipulative capabilities.

A Blue Jay perched on a branch in a snowy environment.

A Blue Jay perched on a branch in a snowy environment.

The Role in Seed Dispersal

Beyond their social interactions and cognitive skills, Blue Jays play a crucial ecological role as dispersers of seeds. They are active participants in collecting and caching nuts and acorns for later consumption, especially during periods of scarce food. A single Blue Jay can cache thousands of nuts annually. What makes their behavior particularly significant is their tendency to transport these nuts over considerable distances, sometimes several thousand meters. This extensive caching behavior inadvertently leads to the germination of many of these forgotten nuts, contributing significantly to the dispersal and propagation of tree species like beech trees. Indeed, Blue Jays are considered largely responsible for the widespread distribution of certain trees across eastern North America following the glacial period.

A Blue Jay holding a peanut in its beak, ready to cache it.

A Blue Jay holding a peanut in its beak, ready to cache it. A map illustrating the distribution range of the Blue Jay across the United States, with different colors indicating summer-only, winter-only, and year-round presence.

A map illustrating the distribution range of the Blue Jay across the United States, with different colors indicating summer-only, winter-only, and year-round presence.

While often admired for their stunning blue plumage, the Blue Jay’s life is rich with complex behaviors that reveal a high degree of intelligence, social sophistication, and ecological importance. Their resourcefulness, communication skills, and role in forest regeneration underscore their significance in the avian world, commanding a newfound respect beyond their striking appearance.

References:

- Stewart PA. 1982. Migration of Blue jays in eastern North America. North American Bird Bander 7:107-112.

- Racine RN and Thompson NS. 1983. Social organization of wintering blue jays. Behaviour 87:237-255.

- Tarvin KA and Woolfenden GE. 1997. Patterns of dominance and aggressive behavior in blue jays at a feeder. Condor 99:434-444.

- Jones, T.B. and Kamil, A.C. 1973. Tool-making and tool-using in the northern blue jay. Science 180, p. 1076-1078.

- Lofton, RW. 1991. Blue jay imitates hawk for kleptoparasitism. Fla. Field Nat. l9(2): 55. 1991.

- Clench, MH. 1991. Another case of blue jay kleptoparasitism. Fla. Field Nat. 19(4): 109-110.

- Johnson, W.C. and Webb, T. III. 1989. The role of blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) in the postglacial dispersal of fagaceous trees in eastern North America. Journal of Biogeography16: 561–571.