Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCM) in dogs, caused by the protozoal parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, presents a serious threat, leading to arrhythmias, heart muscle damage, heart failure, and even sudden death. Understanding the nuances of this disease and the available Antiparasitic Medication For Dogs is crucial for early detection and effective management. This article delves into the complexities of Chagas disease in canines, exploring treatment strategies and the ongoing need for advanced research.

Understanding Chagas Disease in Dogs

Chagas disease, a zoonotic illness prevalent in the Western Hemisphere, is transmitted by specific insect vectors known as “kissing bugs.” In dogs, like in humans, the infection progresses through distinct phases. While some dogs may remain asymptomatic carriers for life, a significant portion can develop chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCM). This condition manifests as irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias), impaired heart function, and can tragically culminate in sudden cardiac death, accounting for a substantial percentage of fatalities in affected animals.

The progression to chronic disease in infected dogs is not fully understood, but research suggests it may mirror the patterns observed in human populations. The challenge in treating T cruzi infection lies in the difficulty of achieving a complete cure and preventing the irreversible cardiac damage associated with CCM.

Challenges in Antiparasitic Treatment for Dogs

Treating Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs presents significant hurdles. While certain medications like benznidazole and nifurtimox have been evaluated, they often come with a high profile of adverse effects at standard dosages. Studies investigating benznidazole in experimentally induced chronic Chagas disease in dogs, even at recommended doses, have shown limited success in preventing the development and progression of CCM. This underscores the ongoing need for research into alternative treatment strategies and improved antiparasitic medication for dogs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends specific treatment protocols for humans, emphasizing its efficacy in acute infections and certain chronic cases. However, translating these human treatment paradigms directly to canines is not always straightforward, necessitating further veterinary research.

Case Studies: Insights into Treatment and Outcomes

This report highlights two distinct cases of severe, symptomatic Chagas cardiomyopathy in dogs, managed with a combination of cardiac medications and antiparasitic treatment. These cases offer valuable insights into the complexities of CCM and the outcomes associated with current treatment approaches, including the use of antiparasitic medication for dogs.

Case 1: An Australian Shepherd’s Battle with CCM

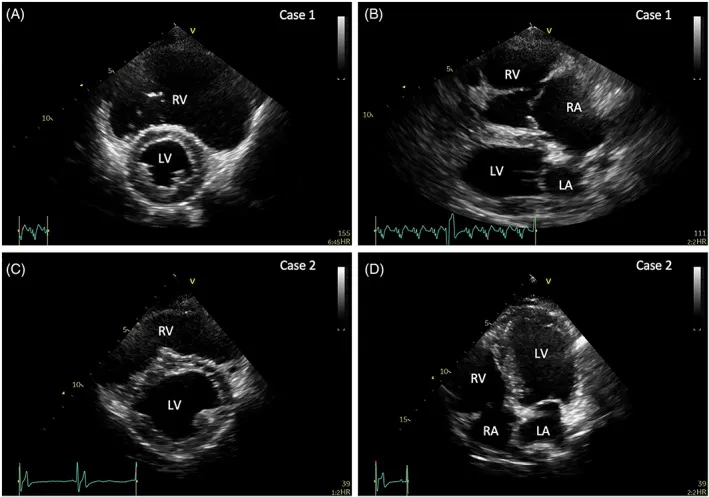

A 9-year-old female spayed Australian Shepherd, residing in South Texas, was referred for cardiology evaluation due to lethargy and suspected cardiomegaly and pleural effusion. Diagnostic assessments revealed significant cardiac abnormalities, including right atrial and ventricular enlargement and complex ventricular arrhythmias. Following a positive T cruzi immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test, the dog was diagnosed with Chagas disease.

Case 1 Echocardiogram

Case 1 Echocardiogram

The treatment regimen included a combination of cardiac medications and the antiparasitic agents amiodarone and itraconazole. While the dog initially showed signs of improvement, unfortunately, she succumbed to sudden death within six months of diagnosis. This outcome emphasizes the aggressive nature of CCM and the limitations of current treatments in preventing fatal events, even with the best available flea tick meds for dogs and antiparasitic options.

Case 2: A Labrador Retriever’s Fight Against Chagas Disease

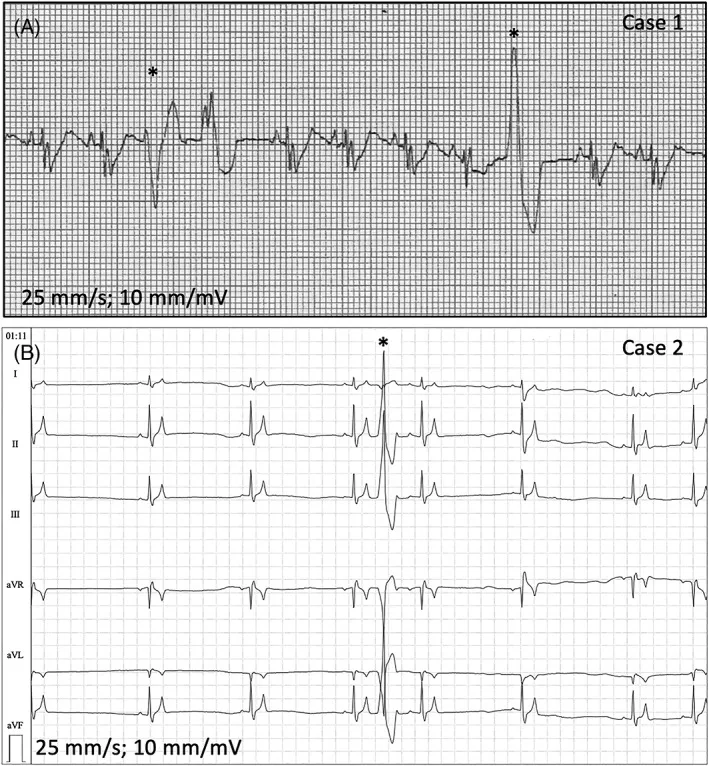

A 5-year-old female spayed Labrador Retriever from Central Texas presented with a history of transient loss of consciousness, indicative of ventricular arrhythmias. Diagnostic workup confirmed Chagas disease with evidence of right heart enlargement and ventricular arrhythmias. The dog was treated with a similar combination of cardiac medications and antiparasitic treatment, including amiodarone and itraconazole.

Case 2 ECG

Case 2 ECG

Despite initial management, this dog also experienced sudden death approximately one month after initiating the amiodarone and itraconazole treatment. These cases highlight the critical need for effective antiparasitic medication for dogs and robust treatment protocols to combat Chagas disease.

Discussion: Navigating the Path Forward

The presented cases underscore the challenges in managing Chagas cardiomyopathy in dogs. While the combination of cardiac medications and antiparasitic treatment with amiodarone and itraconazole showed promise in managing clinical signs and potentially extending survival in previous studies, these outcomes were not achieved in these specific instances. The severity of the cardiac damage and the irreversible nature of myocyte damage, coupled with relatively short treatment durations, may have limited the effectiveness of the antiparasitic therapy.

Risk Factors and Prognosis

Sudden cardiac death is a significant concern in Chagas disease, affecting both humans and canines. In humans, risk scores have been developed to predict sudden death, incorporating factors such as heart failure severity, cardiomegaly, ventricular arrhythmias, and abnormal ECG findings. Similarly, in dogs with CCM, right ventricular enlargement and high-risk ventricular arrhythmias are associated with poorer prognoses. Developing similar risk assessment scores for dogs could be instrumental in predicting survival and identifying those at higher risk of sudden death.

The Role of Antiparasitic Medication for Dogs

The antiparasitic dosing protocols for medications like amiodarone and itraconazole in dogs with Chagas disease are still under investigation. It remains unclear whether these treatments can effectively clear or suppress the infection. Furthermore, both amiodarone and itraconazole carry potential risks, including proarrhythmia and the prolongation of the QT interval, which can increase the risk of fatal ventricular arrhythmias. While adverse effects were noted in one of the reported cases, potentially linked to itraconazole, the other dog tolerated the medications well.

It is important to note that T cruzi parasitemia can be intermittent, and negative PCR results alone should not be solely relied upon to declare a dog free of infection. Cross-reactivity with other parasitic diseases, such as Leishmania, can also occur in serological tests, necessitating careful interpretation in endemic regions.

Future Directions and Hope

Early detection of Trypanosoma cruzi infection and the development of more effective antiparasitic medication for dogs are paramount to improving patient outcomes. Continued research into novel treatment strategies, optimized dosing protocols, and improved diagnostic tools is essential to combat Chagas disease in canines. For owners seeking to protect their pets from common parasites, exploring options for most effective dog flea and tick treatment can be a proactive step. Additionally, understanding how to prevent ticks on dogs is a vital part of responsible pet ownership. When dealing with parasitic infections, consulting with a veterinarian about the best flea tick meds for dogs or exploring advanced treatments like prescription flea treatment for dogs is highly recommended. For other parasitic concerns, information on mange mites treatment may also be relevant.

Conclusion

The cases presented highlight the profound impact of Chagas cardiomyopathy on canine health and the ongoing challenges in its treatment. While current antiparasitic medications and cardiac support offer some management benefits, the high mortality rate due to sudden death remains a significant concern. Continued research and vigilant veterinary care are crucial for improving the prognosis and quality of life for dogs affected by this devastating parasitic disease.

References

Malcolm EL, Saunders AB, Vitt JP, Boutet BG, Hamer SA. Antiparasitic treatment with itraconazole and amiodarone in 2 dogs with severe, symptomatic Chagas cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2022;36(3):1100‐1105. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16422