The legend of the “Alpha Dog” has permeated dog training and popular culture for decades, painting a picture of a pack leader who must be dominated to achieve obedience. But what is the truth behind this concept, and does it hold up to scientific scrutiny? If you’ve ever wondered about the real story behind the alpha dog, prepare to have your perceptions challenged. We’ll delve into the origins of this theory, explore the scientific evidence that has emerged, and discuss more effective, modern approaches to understanding and working with your canine companions.

The Genesis of the Alpha Dog Theory

The idea of the alpha dog largely stems from studies conducted in the wild, most notably by Rudolph Schenkel in the 1940s on captive wolves. Schenkel observed a hierarchical structure within the wolf pack, with a dominant male and female at the top, whom he labeled “alphas.” This model was later popularized and applied to domestic dogs by figures like Cesar Millan, who presented the alpha-dog concept as a direct parallel to wolf pack dynamics. The prevailing advice was that dog owners needed to establish themselves as the “alpha” or pack leader, often through forceful methods, to ensure their dog’s compliance and prevent behavioral issues. This approach suggested that a dog’s misbehavior was a sign of rebellion against the human’s leadership, requiring a firm hand to reassert dominance. This narrative, while compelling, has since been re-examined and largely debunked by further research.

Challenging the Canine Hierarchy: New Scientific Perspectives

Subsequent research, particularly by David Mech, a wolf biologist who initially popularized the alpha concept, has significantly altered our understanding of wolf social structures. Mech’s later work, based on more extensive studies of wolves in their natural habitat, revealed that the “alpha” status in wild wolf packs is not achieved through dominance and aggression, but rather through parentage. In a natural wolf pack, the leaders are the breeding male and female – the parents of the group. The “dominance” observed was akin to that of human parents managing their children, not a constant battle for supremacy.

This crucial distinction has profound implications for how we view dog behavior. Dogs, having been domesticated for thousands of years, are not simply miniature wolves. Their social structures, while sharing some similarities, have evolved differently. Applying a model derived from wild wolf packs, especially one based on a flawed initial interpretation, to the complex relationship between humans and their pet dogs is a misapplication of scientific findings. The idea that a dog is constantly trying to “dominate” its owner is not supported by modern ethology.

Understanding Dog Behavior: Beyond Dominance

If not dominance, then what drives dog behavior? Modern understanding focuses on a more nuanced approach, emphasizing learning theory, communication, and the dog’s emotional state.

Positive Reinforcement and Building Trust

Instead of focusing on establishing dominance, contemporary training methods prioritize positive reinforcement. This involves rewarding desired behaviors with treats, praise, or toys, making the dog more likely to repeat those actions. This approach not only encourages good behavior but also strengthens the bond between dog and owner. It’s about building a partnership based on mutual respect and clear communication, rather than an assertion of power. When dogs learn that good things happen when they listen, they are more motivated to do so.

Communication and Body Language

Dogs communicate through a sophisticated array of body language, vocalizations, and scent. Understanding these signals is key to effective communication. Rather than interpreting a dog’s actions as attempts to dominate, it’s more productive to understand what they might be communicating. For instance, a dog showing appeasement behaviors like lip licking or averting their gaze might be feeling anxious or uncomfortable, not trying to be “the boss.” Learning to read these subtle cues allows owners to respond appropriately to their dog’s needs and emotions.

Addressing Behavioral Issues with Modern Techniques

When behavioral problems arise, such as excessive barking, jumping, or resource guarding, the focus shifts from asserting dominance to identifying the underlying cause. Is the dog bored? Anxious? Lacking exercise or mental stimulation? Are their needs being met? For example, a dog that barks incessantly at the door might be reacting to a lack of appropriate outlets for their energy or a learned association with attention. Training interventions would then focus on redirecting that energy, teaching a “quiet” cue, or addressing any underlying anxiety. Modern techniques often involve desensitization, counter-conditioning, and teaching alternative behaviors.

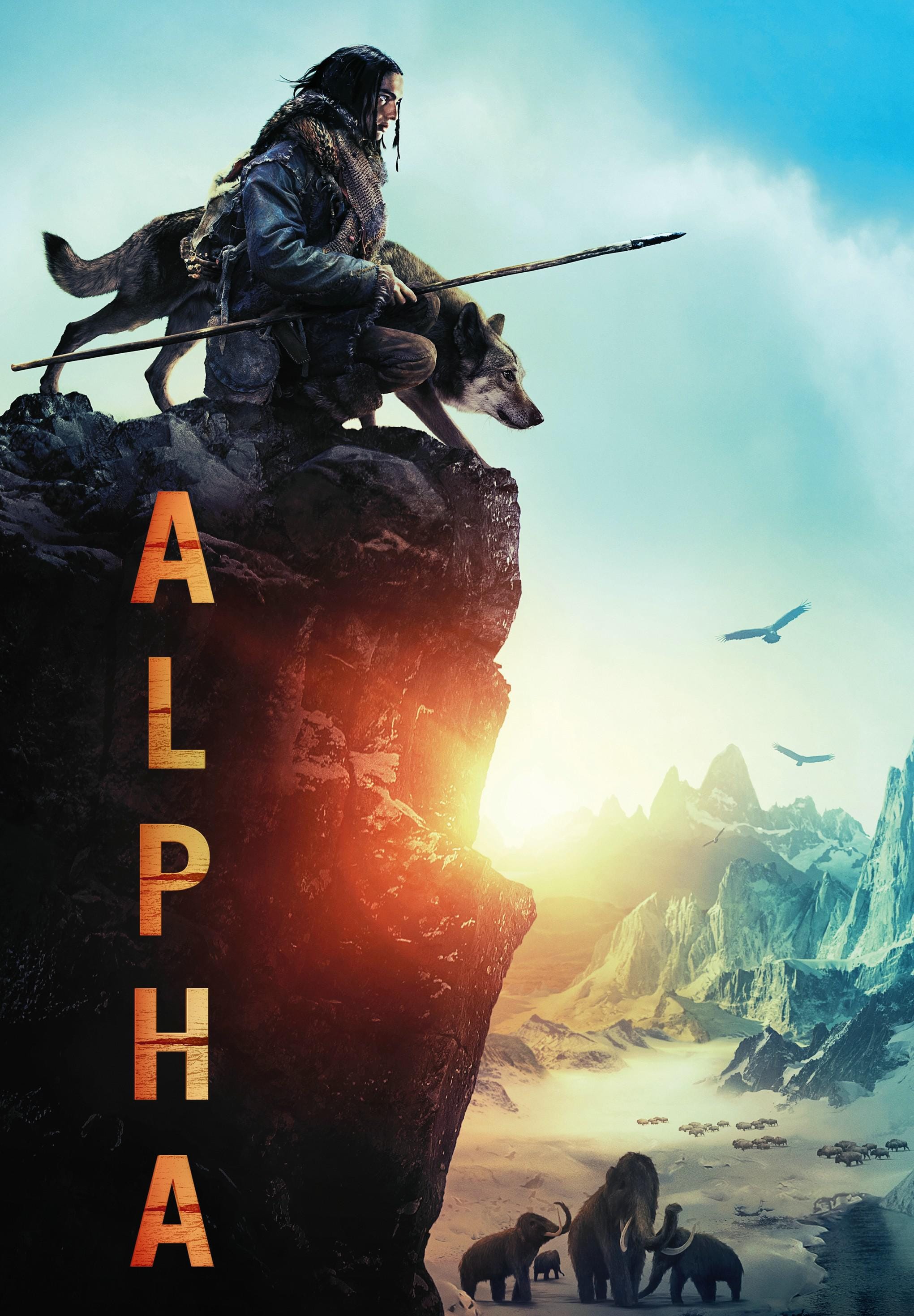

The “Alpha Dog” Movie: A Fictionalized Account

It’s worth noting that the popular movie “Alpha” (2018) is set in the Paleolithic era and offers a fictionalized, albeit visually stunning, portrayal of early human-dog partnerships. While it explores themes of survival and bonding, it is a dramatization and not a documentary reflecting accurate historical or scientific data on dog domestication or training principles. The film’s narrative, like many other portrayals, contributes to the mystique surrounding the “alpha” concept, but it should not be taken as a guide for real-world dog behavior and training. The true story of our canine companions is far more complex and rewarding than a simple dominance hierarchy suggests.

Embracing a Partnership with Your Dog

The journey of understanding our dogs is an ongoing one. The outdated “alpha dog” model, rooted in a misinterpretation of wolf behavior, has given way to more compassionate, effective, and scientifically sound approaches. By focusing on positive reinforcement, clear communication, and understanding our dogs as the unique, sentient beings they are, we can build stronger, more fulfilling relationships. This partnership, built on trust and mutual respect, is the true hallmark of a successful human-dog bond, far more valuable than any assertion of dominance.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dog Behavior

Q: Is the “alpha dog” concept completely false?

A: The strict application of the “alpha dog” theory, as popularized in dog training, is largely considered outdated and misinformed by modern ethologists. While there are social dynamics within dog groups, it’s not a direct parallel to a forced dominance hierarchy over humans.

Q: How should I establish myself as a leader for my dog?

A: True leadership with your dog comes from consistency, clear communication, and providing for their needs. It’s about being a reliable source of guidance and positive experiences, not about asserting dominance.

Q: What are the best ways to train my dog without using dominance?

A: Positive reinforcement methods are highly effective. This includes rewarding good behavior, using clear cues, managing the environment to prevent unwanted actions, and understanding your dog’s motivations and emotional state.

Q: My dog seems to challenge me sometimes. What does this mean?

A: This often indicates a lack of clear communication, unmet needs (like boredom or anxiety), or a learned behavior. Instead of seeing it as a challenge for dominance, try to identify the root cause and address it with training and management.

Q: How does understanding wolf behavior help with dog training?

A: While dogs are not wolves, understanding wolf social structures (especially the more recent findings about family-based hierarchies) can offer some insights into canine social cognition. However, it’s crucial to remember the significant differences due to thousands of years of domestication.

Q: Are there any situations where understanding pack dynamics is relevant for dogs?

A: Yes, when multiple dogs live together, understanding social dynamics can be helpful. However, this is about observing natural interactions and managing relationships, not imposing an “alpha” role.

Q: What is the modern, scientifically backed approach to dog behavior?

A: The modern approach emphasizes learning theory (positive reinforcement, classical conditioning), understanding canine communication and ethology, and building a strong, trusting relationship through clear and consistent guidance.